Halifax prospers despite its connection with three horrific 20th-century transportation disasters

USA Today — June 14, 2022

HALIFAX, Nova Scotia – The natural beauty of this Canadian province in the north Atlantic belies the horrific tragedies inextricably linked to the island’s past.

The harbor in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Nova Scotia has a connection with three of the world’s worst transportation accidents of the 20th century – the sinking of the Titanic, a Swissair plane crash and a harbor accident that killed more than 1,600 people in the deadliest human-caused explosion prior to the atomic age.

It’s easy to understand why some still call Halifax “the city of sorrow.”

The Fairlawn View Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where 121 Titanic victims are buried, more than any other cemetery in the world.

During an early May trip to Nova Scotia, I visited several sites related to the three disasters and learned how the province has not only endured but prospered.

Nova Scotia isn’t defined by tragedy. With a rich maritime history, cosmopolitan seaport, tourist-friendly locals and one of the most picturesque lighthouses in North America, it was my favorite stop on a 10-day cruise through New England and eastern Canada.

I sailed on the American Queen Voyages’ Ocean Voyager, a 202-passenger ship that was less than a quarter full – just 49 passengers with a crew of 86.

“If you drop a napkin, there will be a crew member to catch it before it hits the ground,” our cruise director Johnny Melnick joked as I boarded the ship in Portland, Maine.

The 202-passenger American Queen Voyages Ocean Voyager docked in Montreal, Canada.

Cruising through eastern Canada

We traveled more than 1,400 miles from Portland to Toronto, sailing on the Atlantic Ocean into the St. Lawrence Seaway before ending on Lake Ontario.

In addition to Nova Scotia, we stopped in Quebec City, Montreal, and the sparsely populated Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. With the help of two onboard naturalists, we spent a day whale-watching in the Saguenay Fjord in Quebec, where we spotted several Beluga whales.

The Cap-Herisse Lighthouse on one of the Magdalen islands in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. The island was one of the stops on a 10-day cruise through New England and eastern Canada.

We followed the Voyager’s sister ship – the Ocean Navigator – which was three days ahead of us on the same itinerary. Once the two ships reached Toronto, they embarked on their summer-sailing season through the Great Lakes.

Located about 300 miles east of Maine, Nova Scotia is one of Canada’s three Maritime provinces – along with New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

The province has 1 million residents, about half of whom live in the capital and largest city of Halifax. Nova Scotia means “New Scotland” in Latin, reflecting its strong historic and cultural connection to Scotland.

Nova Scotia and the Titanic

While on its maiden voyage from England to New York in April 1912, the HMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sunk in the north Atlantic. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died. It remains the deadliest peacetime sinking of a superliner or cruise ship.

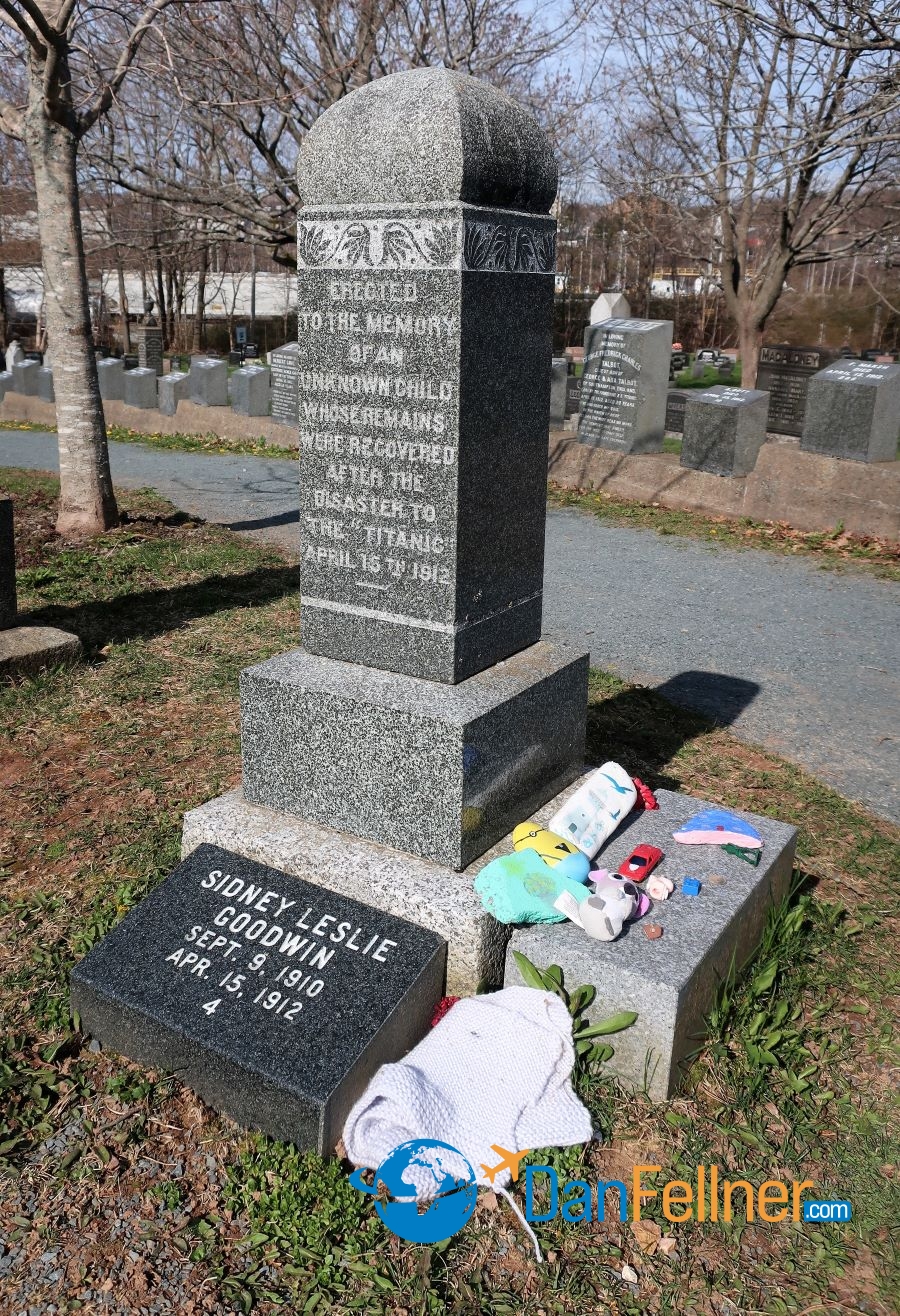

The grave at Halifax’s Fairview Lawn Cemetery of a 19-month-old boy who drowned in the Titanic disaster.

Nova Scotia became the epicenter of recovery efforts. The White Star Line, which owned the Titanic, chartered several ships from Halifax to aid in the search and rescue operations. So many bodies were recovered and brought back to Halifax that the city converted an ice rink into a morgue. Today, 150 victims are buried in three Halifax cemeteries.

I visited the Fairlawn View Cemetery on the city’s north side, where 121 Titanic victims are interred, more than any other cemetery in the world. The people buried in one-third of the graves have never been identified and are marked only with a number and date of death – April 15, 1912.

The leather shoes worn by Titanic victim Sidney Leslie Goodwin on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

It was especially moving to visit the gravesite of a 19-month-old boy, originally known as “the unknown child.” In 2001 the boy’s body was exhumed in an attempt to learn his identity. He was initially misidentified as a Finnish child. In 2007, more advanced testing determined he was Sidney Leslie Goodwin, the youngest in an English family of eight on the ship. None of Sidney’s family members survived.

At the base of his grave, I observed a small blanket, children’s clothing and toys. Our guide told us that visitors place so many items at Sidney’s grave to honor his memory that cemetery caretakers have to clear them off at least twice a week.

The leather shoes the boy was wearing when his body was recovered are on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic on Halifax’s waterfront, which has one of the largest collections of Titanic artifacts in the world.

The 1917 Harbor Explosion

An exhibit about the 1917 harbor explosion at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

Just over five years after the Titanic sunk, Halifax was the site of another tragedy. On the morning of Dec. 6, 1917, the Mont-Blanc, a French ship carrying a large cache of explosives, collided with a Norwegian vessel in the city’s harbor.

The collision resulted in a massive explosion that killed more than 1,600 people, injured 9,000 others and flattened more than one square mile of the city. It remains the biggest disaster in Canadian history.

There is a comprehensive exhibit devoted to the harbor explosion at the Maritime Museum, and several monuments and works of art around the city pay tribute to the victims. The clock at Halifax City Hall near the waterfront is permanently set at 4 minutes and 35 seconds after 9, the exact time of the explosion.

The clock at the Halifax City Hall in Nova Scotia is permanently set at four minutes and 35 seconds past 9:00, the exact time of the 1917 harbor explosion that killed more than 1,600 people.

Crash of Swissair Flight 111 Near Peggy’s Cove

The tiny fishing village of Peggy’s Cove, 26 miles southwest of Halifax, is the site of one of the most recognizable lighthouses in the world – the iconic Peggy’s Point Lighthouse. Built in 1915, the 50-feet-high, red-and-white beacon is perched on an outcrop of granite rocks. It’s still a working lighthouse and is operated by the Canadian Coast Guard.

In 1998, Swissair Flight 111 – en route from New York to Geneva – crashed 5 miles off the coast of Peggy’s Cove. All 229 passengers and crew members were killed. An investigation determined the crash was caused by an in-flight fire.

The iconic Peggy’s Point Lighthouse southwest of Halifax.

Once again, Nova Scotia became the hub of search and recovery operations for a transportation disaster.

From the lighthouse, I hiked a mile along the coast to pay my respects to the victims at a memorial overlooking the sea. Part of the inscription etched into a large gray stone – written in both English and French – read: “They have been joined to the sea and the sky.”

A memorial to the 229 victims of Swissair Flight 111 which crashed in 1998 near Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia. The area was used as a staging ground for search and rescue operations.

While I thought about the victims who perished nearby, I could see the lighthouse in the distance. The contrast of two sites in such close proximity – one serene and alluring, the other a reminder of a calamitous accident – was difficult to grasp.

As I walked from the Swissair memorial to join my fellow passengers back on the tour bus, a cold front blew in from the Atlantic, bringing biting wind and freezing rain.

Reflecting on the tragedies I had learned about during my time in Nova Scotia, the gloomy weather seemed only fitting.

Websites for more info:

Tourism Nova Scotia

American Queen Voyages

A drill team wearing Scottish kilts marches at the Halifax Citadel.

© 2022 Dan Fellner