Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center a $50 million high-tech showcase of Jewish life in Russia through the centuries

Jewish News of Greater Phoenix — July 28, 2017

MOSCOW, Russia — It’s been open less than five years but the venue already has been labeled by some as the most important Jewish cultural site in all of Europe.

Entrance to the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow, which is housed in a former bus garage.

After spending a July afternoon inside Moscow’s tastefully designed, informative and high-tech Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, the moniker seems well-deserved.

The museum, housed inside a former bus garage built in the 1920s in a northwest Moscow neighborhood, opened in 2012 at an estimated cost of $50 million. It’s a must-see for Jewish visitors to Russia’s capital city who want to learn about their ancestors’ complex, up-and-down history in a part of the diaspora that once was home to the largest Jewish population in the world.

My visit to the museum was a highlight of a two-week Volga river cruise on the Scenic Tsar that began in Moscow and ended in St. Petersburg. On my first free afternoon in Moscow, I toured the facility and met with Anna Sokolova, the head of the museum’s research center.

Before the war with Ukraine and the resulting sanctions, the museum attracted about 300,000 visitors a year.

She told me that the museum was built with the strong support of the Russian government. Even President Vladimir Putin personally donated one month of his salary – about $10,000 – for construction. Since the opening, Putin has visited the museum several times.

“It showed that it’s really important to the Russian government to fight anti-Semitism and that the Jewish community is a very important part of the country,” says Sokolova, who speaks five languages, including Hebrew.

Last year, the museum attracted 300,000 visitors, up a whopping 50 percent from the prior year. Even more growth is anticipated in the coming year. With the approval of Russia’s Ministry of Education, the museum is launching a program in September in which all middle-school children in Moscow will be required to visit the venue as part of a school fieldtrip. It’s a huge leap from an era in which Jewish history and culture was rarely discussed in public schools.

“It was mainly forbidden during Soviet times, so it’s really important to speak about it now,” says Sokolova.

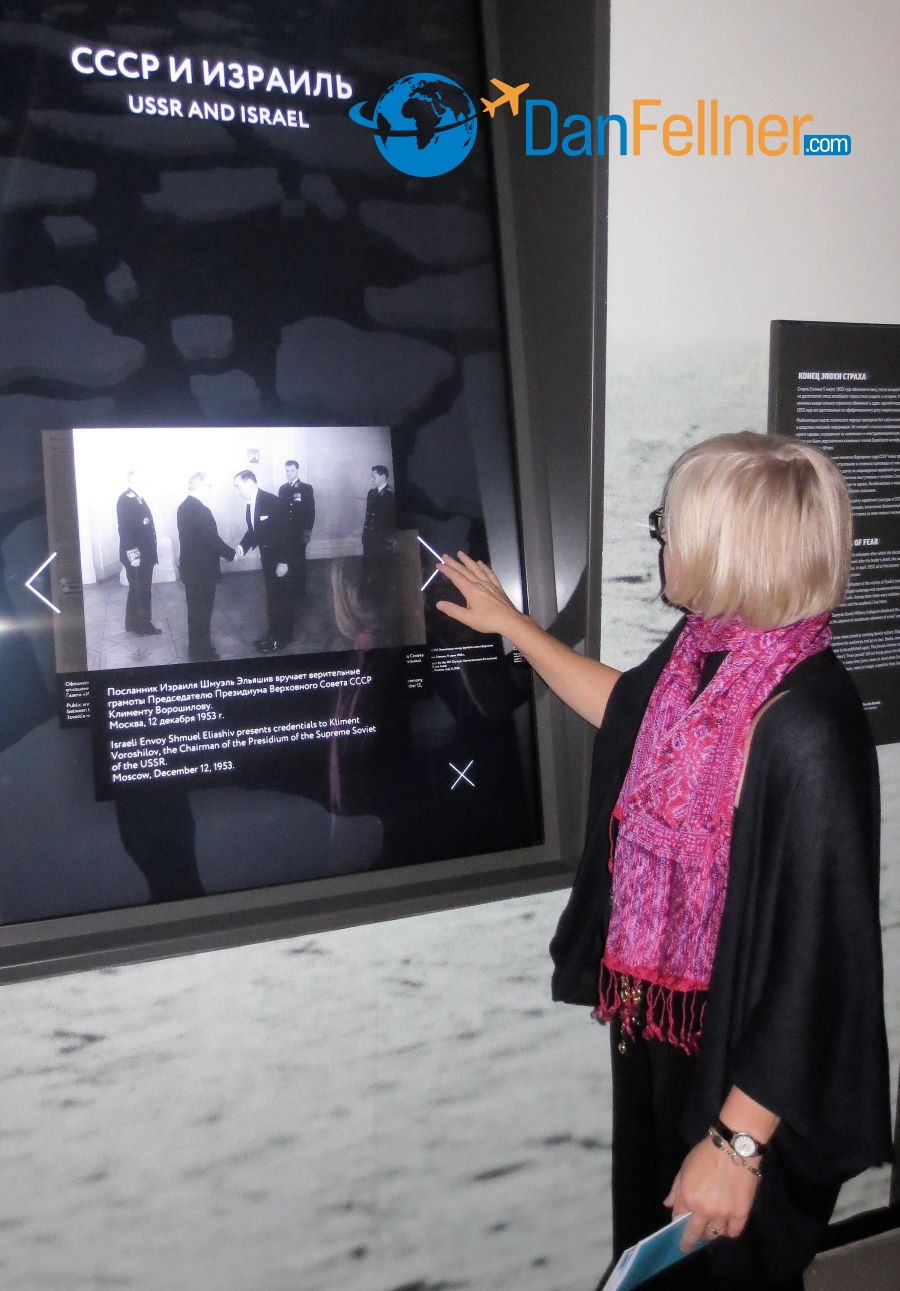

Exhibits at the museum are high-tech and interactive.

Using panoramic films, interactive screens and numerous artifacts, the museum chronicles Jewish history dating back to the rule of Catherine the Great in the 18th century. There are exhibitions devoted to the origins of Russian Jewry, the role Jews played in the 1917 revolution, the Holocaust, and a section called “Perestroika to the Present.”

I especially enjoyed strolling through a recreated shtetl from the 19th century, which included a small synagogue, Shabbat table, Jewish school and marketplace. It’s one of the museum’s most popular exhibits.

“The shtetl became the heart of Judaism and it helped people to keep their traditions alive,” says Sokolova.

The shtetl even included an exhibit in which visitors could have their photos taken and then digitally integrated with the costume of a profession of their choice, such as a tailor, matchmaker, musician, teacher or blacksmith. I chose to digitally don the garb of a 19th century rabbi.

The author digitally dons the garb of a 19th-century Russian rabbi at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow.

Indeed, the museum was designed to keep visitors as engaged as possible with most exhibits featuring some type of interactivity.

“The idea was to create something in the form of ‘edutainment’ – education and entertainment together,” says Sokolova. “The format is designed to be very interesting for every age.”

In a partnership with the Russian State Library, the museum also houses the “Schneerson Collection,” which includes significant and once inaccessible works of the Lubavitcher rebbes dating back to the late 18th century. The collection was nationalized by the Russian government during the Communist period; it was moved to the Jewish Museum in 2013.

The “Schneerson Collection” at the Jewish Museum includes significant and once inaccessible works of the Lubavitcher rebbes dating back to the late 18th century.

In addition to its permanent collection, the museum houses about a half-dozen temporary exhibits a year, some of which are on non-Jewish topics. Exhibits are mostly in Russian, although some also contain English descriptions. The venue is open every day except Saturdays and Jewish holidays. For more information, visit the museum’s website: www.jewish-museum.ru/en.

Accounts vary about the current size of Russia’s Jewish population as many people with Jewish roots don’t practice their faith and have intermarried. But it’s estimated that about 200,000 Jews remain in the country, making it the third-largest Jewish community in Europe. Most Jews live in Moscow and its surrounding communities, where there are about 20 working synagogues.

“We are seeing since the 1990s many people are coming back to Jewish traditions and to their roots, which were almost killed in the Soviet Union,” says Sokolova.

The Grand Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg, the second-largest synagogue in Europe.

Two weeks later, at the end of the Volga River cruise on the Scenic Tsar, I had the chance to visit St. Petersburg’s stunning Grand Choral Synagogue. It’s the second-largest synagogue in Europe (Budapest is home to the largest).

Consecrated in 1893, the Moorish-styled building is a registered national landmark. It can accommodate up to 1,200 worshippers at one time; the complex also houses a kosher restaurant and supermarket.

My grandparents immigrated from Russia, so the Jewish sights in Moscow and St. Petersburg held special meaning. Despite the challenges my ancestors and other Jews faced in Russia, it was especially heartwarming to learn that Jewish life in the country has not only endured over the centuries, but now even seems to be enjoying a modest revival.

“We can see that the Jews managed to keep their traditions despite all the pogroms and despite state politics, which was quite often pretty anti-Semitic,” says Sokolova. “The situation in Russia has changed drastically. The Jewish community feels free now.”

The beautiful interior of the Grand Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg.

© 2017 Dan Fellner