Skopje’s Jewish community survives despite near annihilation during the Holocaust

June 20, 2019

SKOPJE, North Macedonia – Like many countries in Eastern Europe, North Macedonia offers visitors wanting a glimpse of Jewish history and culture a bittersweet experience.

The Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of Macedonia.

There are remnants and artifacts of a once-thriving community, which dates back to Roman times and ultimately reached a peak of nearly 12,000 Jews before World War II.

There are inspirational signs of survival and a modest rebirth, namely in the form of the newest synagogue in the Balkans, Beit Yaakov, a Sephardic-style synagogue with beautiful stained-glass windows designed by local artists.

There also is a deeply disturbing and moving museum chronicling the virtual destruction of Macedonia’s Jewish community during the Holocaust, when more than 7,000 Jews were transported to their deaths at the concentration camp in Treblinka, Poland.

Inside Skopje’s Beit Yaakov synagogue, the only Jewish house of worship in North Macedonia.

I recently spent six weeks teaching at North Macedonia’s largest university and had an opportunity to learn more about the roller-coaster existence of the region’s Jewish community.

Macedonia, as the locals call it, was officially renamed the Republic of North Macedonia in early 2019 to resolve a decades-old dispute with neighboring Greece, which had long laid claim to the name of Macedonia. It’s believed the move will pave the way for the country to eventually join the European Union and the NATO military alliance.

The stained-glass windows inside Skopje’s Beit Yaakov synagogue were designed by local artists.

Skopje, a city of a half-million people, is the capital of this landlocked country about the size of Vermont. Macedonia gained its independence when Yugoslavia imploded in the early 1990s. The country’s Macedonian majority is mostly Eastern Orthodox; however, ethnic Albanians – many of whom practice Islam — constitute about 25 percent of the country’s population.

Today, the country’s Jewish population has dwindled to about 200. Virtually all of them live in Skopje.

On my second day in the city, I visited the Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of Macedonia, a $23 million state-of-the-art and tastefully designed museum located in the heart of what once was the city’s Jewish quarter. It’s just a stone’s throw from two of Skopje’s most famous sites – the historic Stone Bridge that takes pedestrians across the Vardar River, and the old Turkish Bazaar.

The Holocaust Museum in Skopje chronicles the prosperous — and tragic — history of Jews in the region.

Inaugurated in 2011, the Holocaust museum was built with money raised from a 2002 law providing for the return of heirless Jewish property to the Jewish community, a law that is widely recognized as one of the best in Europe.

Inside the museum, I learned that the first-known synagogue in Skopje dates back to 1366. Many Jews came to the region following the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions. The Jewish community was almost entirely Sephardic, and most spoke Ladino at home. When Macedonia was part of the Ottoman Empire, Jews prospered in the fields of trade, banking and medicine. They also enjoyed fairly good relations with the non-Jewish population. At one point, there were 14 working synagogues in the country, nine of them in Bitola, a city in southern Macedonia that is close to the Greek and Albanian borders.

A German cattle-car that was used to transport Macedonia’s Jews to Treblinka. It’s one of the displays at the Skopje Holocaust Museum.

The museum has a number of multimedia exhibits depicting Jewish life in Macedonia and the Balkans through the centuries, including historic Jewish religious and cultural artifacts. Most of the exhibits are in English.

In 1941, the Bulgarian army entered what is now Macedonia in an effort to reclaim the region, which it believed was part of its own homeland. During its occupation, the Bulgarians implemented anti-Semitic laws and began to force the Jews into ghettos and slave-labor camps. In 1943, under orders from Germany, Bulgarian troops deported most of Macedonia’s Jews to the Yugoslav border with Romania, where they ultimately were transported in cattle-cars by Germans to the death camp in Treblinka, Poland.

To Bulgaria’s credit, its government succumbed to public and political pressure and refused to hand over the Jews in its own territory to the Germans. Sadly, the Jews of Macedonia were not so fortunate. None of the more than 7,000 men, women and children survived the deportation to Treblinka.

A haunting monument remembering the Jewish victims outside the Holocaust Museum in Skopje, North Macedonia.

The World Jewish Congress has noted that no Jewish community in Europe suffered a greater degree of destruction than the one from North Macedonia. Less than 2 percent of the country’s Jewish population survived the Holocaust.

Perhaps the Holocaust museum’s most haunting and impactful exhibit is a German cattle-car that transported the Jews to their deaths. Stepping inside the dark, wooden structure, one can only imagine the inhumane conditions and sheer horror the Jews endured before being murdered by the Nazis in the gas chambers.

Outside the museum stands a powerful and evocative statue of two young Jews, heads bowed in grief, next to packed suitcases and shoes. In the process of being uprooted from their home, they are seemingly on their way to a ghetto or concentration camp.

While few of the country’s Jews survived the Holocaust, the community somehow managed to endure. The rebirth culminated in the construction of a new synagogue in 2003, the only Jewish house of worship in North Macedonia.

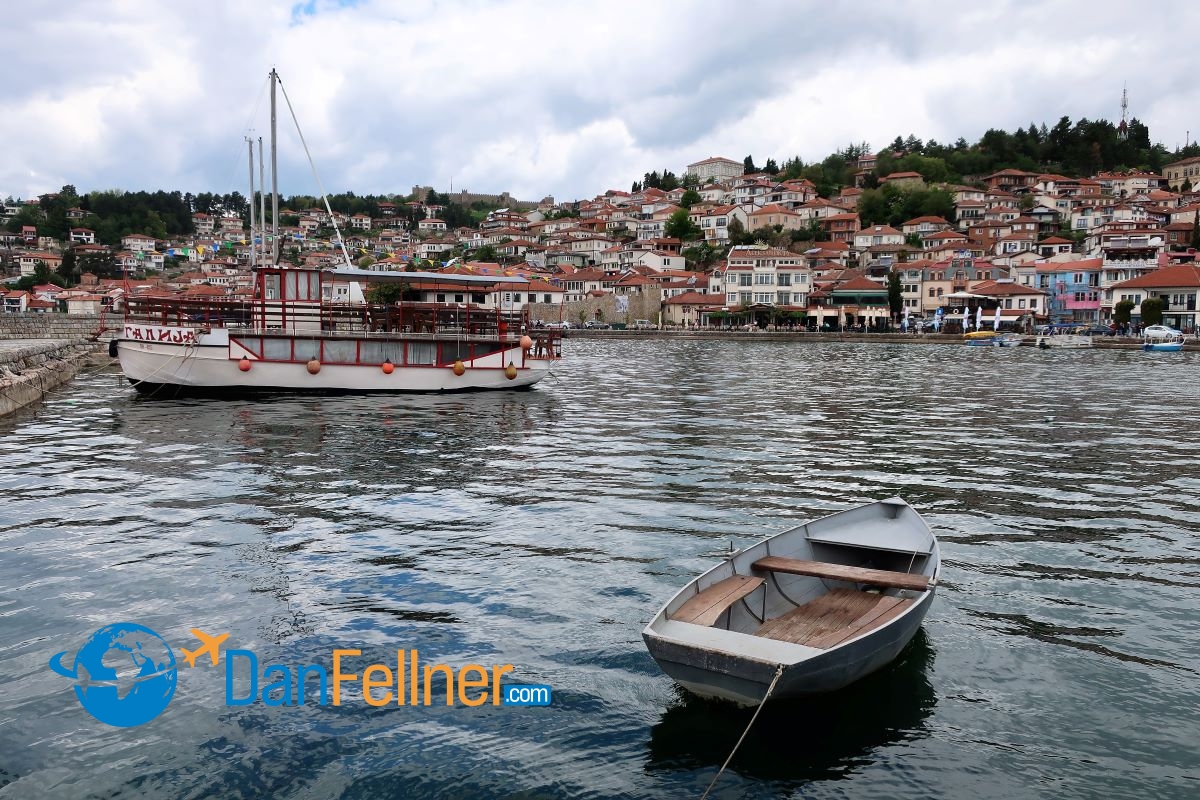

Lake Ohrid in southwestern North Macedonia. The country has largely been spared from the wave of anti-Semitism that is creeping across Europe.

A 15-minute walk from the museum, Beit Yaakov is located on the top floor of a non-descript three-story building that also houses the Jewish community’s administrative offices and rooms for a small religious school and community events.

During my visit to the synagogue, I met with Jana Nichota, the secretary general of the Jewish community. She told me that while Skopje’s Jews strongly embrace their history and culture, they aren’t particularly religious.

It’s a symptom of Jewry throughout Eastern Europe, where Jewish communities, decimated by the Holocaust, became less observant during Socialist times, mainly because religion — of any type — was largely frowned upon by ruling governments.

Indeed, the Skopje synagogue has no rabbi and rarely holds services. Normally, a rabbi is brought in from Belgrade or another location to lead High-Holiday services. But this past year, Jana said, there just wasn’t enough interest. However, the community did host a Passover Seder in April, with about 30 attendees.

The famous Painted Mosque in Tetovo dates back to 1438. North Macedonia has a large Muslim population.

North Macedonia has largely been spared from the wave of anti-Semitism that is creeping across Europe. The small population of Jews gets along well with its Christian and Muslim neighbors. The country’s president and prime minister — along with leaders of the Orthodox, Catholic and Muslim communities — attended the inauguration of the Holocaust museum.

“If you build it, they will come,” goes the line from the movie “Field of Dreams.” With a beautiful 21st-century synagogue and a Jewish museum that outshines exhibitions in much larger European cities, Skopje’s Jewish leaders hope their once dormant community will continue to regain its footing and attract visitors to learn more about Jewish life in a little-understood part of the world.

© 2019 Dan Fellner