Texas island offers much to see related to the Galveston Movement, a pivotal chapter in Jewish-American history

JTA/Jerusalem Post — November 26, 2025

GALVESTON, Texas — More than a century ago, this busy Gulf Coast port and longtime vacation destination 50 miles southeast of Houston welcomed so many European immigrants – including some 10,000 Jews – it earned the moniker “The Ellis Island of the West.”

Galveston’s historic downtown. The island-city is home to about 53,000 people.

Today, the few remaining descendants of Jewish immigrants from that time period still living on the island are determined to preserve and nourish the story of the Galveston Movement, a mostly forgotten but pivotal chapter in Jewish-American history.

Galveston, an island-city of 53,000 residents, is the fourth busiest cruise port in the country and the birthplace of the Juneteenth holiday, which commemorates the end of slavery in the U.S. With 32 miles of brown-sand beaches, a charming historic district with numerous well-preserved Victorian-era homes, and some 80 festivals held year-round, the island annually attracts 8 million tourists.

Galveston Island, a popular vacation destination 50 miles southeast of downtown Houston, has 32 miles of brown-sand beaches.

It also offers visitors several sites related to the Galveston Movement and what was once a surprisingly robust Jewish community that produced five mayors, prominent business leaders and two highly renowned rabbis.

The Galveston Movement, also called the Galveston Plan, was a humanitarian effort operated by several Jewish organizations that brought Jewish immigrants from Czarist Russia and Eastern Europe through the port of Galveston between 1907-14. Most arrived in Galveston on steamships from Bremen, Germany, a transatlantic trip that took 2-3 weeks.

A 5,000-square-foot mural in downtown Galveston illustrates the journey of Black Americans to freedom. Galveston is considered the birthplace of Juneteenth, which commemorates the end of slavery.

A recent book by English historian and journalist Rachel Cockerell — Melting Point – has helped reignite interest in the Galveston Movement. Cockerell’s great-grandfather David Jochelmann played a central role in organizing the program in Europe. Cockerell recently spoke at Galveston’s Temple B’nai Israel as part of a U.S. tour promoting the book.

“As soon as started reading about the Galveston Movement, I sort of went down a rabbit hole from which I didn’t emerge for three years,” Cockerell told a group of more than 100 Galvestonians, Jews and non-Jews alike. “I was totally transfixed by this amazing story of Jewish immigration in the early 20th century.”

“I love it,” says Shelley Nussenblatt Kessler, 74, of the heightened attention on the Galveston Movement. Kessler estimates she is one of 25-30 “BOIs” (born on the island) still living in Galveston who are descendants of the Jewish immigrants who came to America as part of the program. Her grandmother and grandfather immigrated from what is now western Ukraine to Galveston in 1910 and 1911.

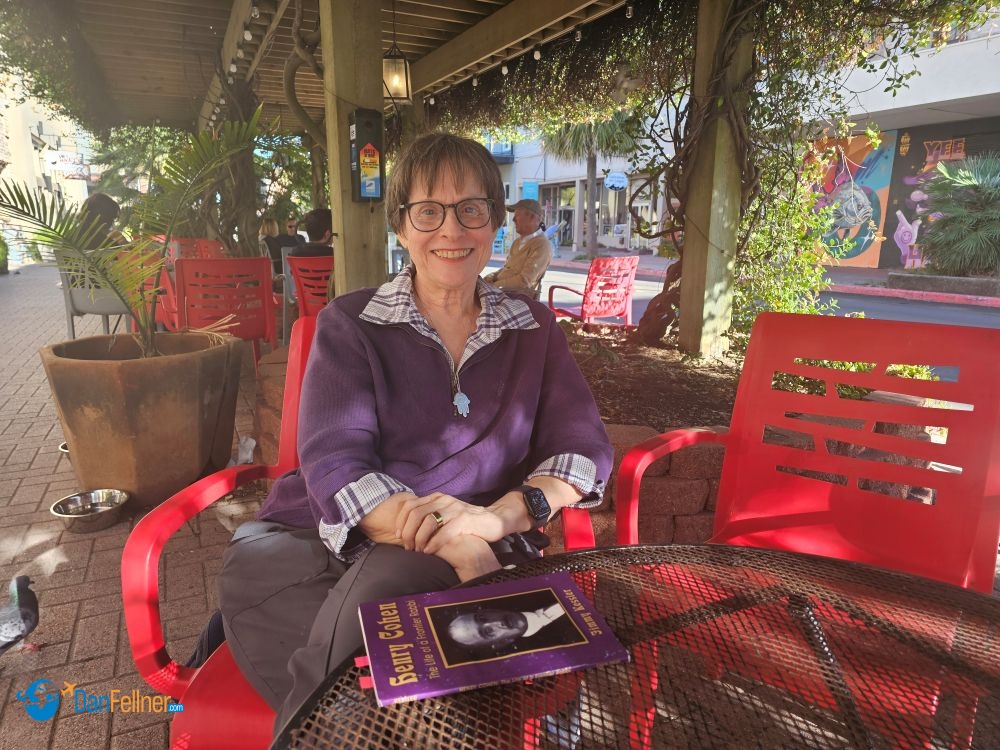

Shelley Nussenblatt Kessler, a descendant of Jewish immigrants who came to America as part of the Galveston Movement in the early 20th century.

“Not only am I very proud to be a descendant of two of these immigrants, but I can’t help but think of how lucky I am to be here,” she says. “I’m in awe of what my grandparents did and how they got here, and the sacrifices that they made.”

By the late 1880s, thousands of Jews began fleeing their homes in the Russian Empire to escape antisemitic policies and violent pogroms. Many immigrated to New York and other East Coast cities, resulting in overcrowding and poverty.

Jacob Schiff, a New York banker and philanthropist, financed the Galveston Movement as a way to prevent an anticipated wave of antisemitism on the Eastern seaboard, which might lead to immigration restrictions. Schiff sought to find suitable alternative destinations in the American South for the influx of Jewish immigrants.

Galveston is the fourth busiest cruise port in the United States. Its deep-water harbor made it an ideal choice as a hub for European immigration.

Charleston, South Carolina, which had a long-established Jewish community, was considered but city leaders there only wanted Anglo-Saxon immigrants. New Orleans was also in the mix but there were concerns about periodic outbreaks of yellow fever.

Enter Galveston, a port that checked all of the boxes. It had a deep-water harbor that could accommodate large ships and an extensive railroad system available to transport immigrants to other cities and towns.

“Really the purpose of Galveston was to channel the immigrants into other parts of Texas and up the middle of the country west of the Mississippi,” says Dwayne Jones, a historian who is CEO of the Galveston Historical Foundation.

B’nai Israel’s original synagogue – built in 1870 – was the spiritual launching point for the Jewish immigrants who were part of the Galveston Movement. It is now a private residence.

Jones says there was another key reason Galveston was selected; there already was a well-established Jewish community that was thriving in the city’s business and political circles. In fact, Galveston had elected its first Jewish mayor — Dutch-born Michael Seeligson — as far back as 1853.

“It was a more tolerant community with a depth of diversity you didn’t see in other places,” Jones says. “It also had a long history of Jewish leadership and activities in Galveston.

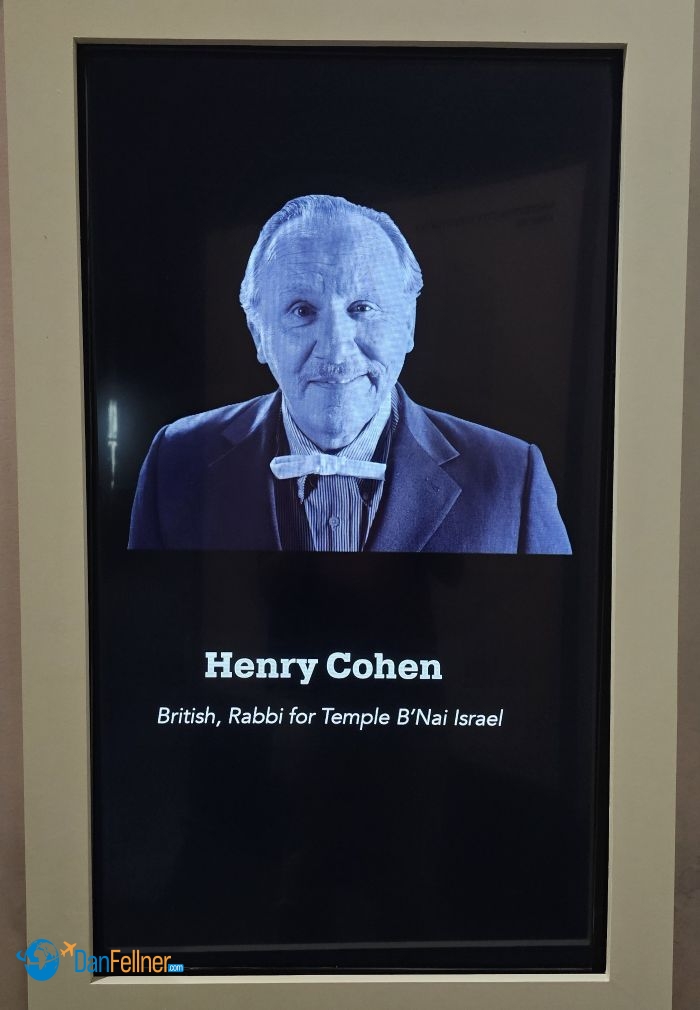

The first Reform congregation in Texas, Galveston’s Congregation B’nai Israel, was established in 1868. Twenty years later, London-born Henry Cohen, who was only 25 at the time, became the congregation’s rabbi. Cohen led B’nai Israel for a remarkable 64 years until his death in 1952. It’s believed to be the longest tenure of a rabbi at the same congregation in U.S. history.

A photo of Rabbi Henry Cohen, the humanitarian face of the Galveston Movement, on display at the Galveston Historic Seaport Museum. Cohen led Congregation B’nai Israel for 64 years until his death in 1952.

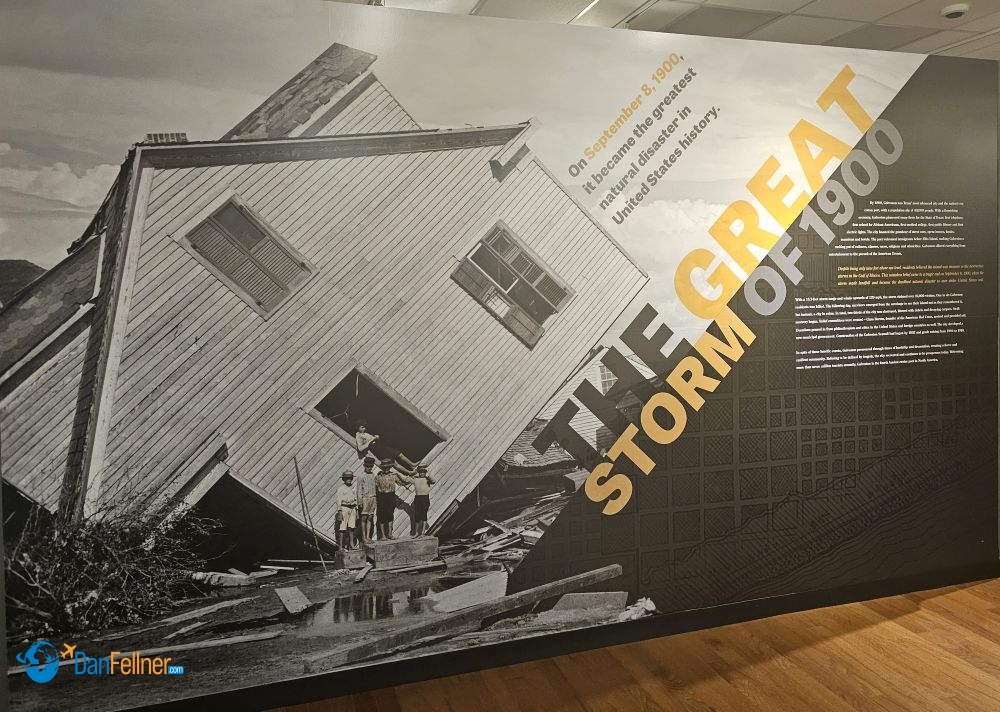

In 1900 Galveston was decimated by a storm known as the Great Galveston Hurricane. It remains the deadliest natural disaster in American history, with an estimated 8,000 fatalities, about 20 percent of its population at the time. Two-thirds of the island’s buildings and homes were destroyed. Cohen and other Jewish leaders played a played a major role in the relief and reconstruction efforts that followed.

“Jewish leadership took a really powerful role in rebuilding the island,” says Jones. “Without that leadership, I don’t think Galveston would have come back as it did.”

A hurricane in 1900 that decimated Galveston remains the deadliest natural disaster in American history.

Seven years after the hurricane, the first ship that was part of the Galveston Movement – the S.S. Cassel – arrived from Bremen with 86 Jewish passengers. Cohen – who was proficient in 10 languages — was the humanitarian face of the movement, meeting ships at the Galveston docks and helping guide the immigrants through the cumbersome arrival and distribution process.

The arrivals were processed at the Jewish Immigrants’ Information Bureau headquarters in Galveston, which gave the immigrants rations and railroad tickets to more than 150 towns in Texas and other places west of the Mississippi River.

Unlike a vast majority of the immigrants who had only a brief stopover in Galveston before settling in other communities, Kessler’s grandparents decided to remain on the island. Her grandfather was a painting contractor while her grandmother worked as a housekeeper.

The current site of Galveston’s Temple B’nai Israel. Founded in 1868, it is the oldest Reform congregation in Texas. Under the leadership of Rabbi Henry Cohen, it played a pivotal role in the Galveston Movement.

Adjusting to life in Texas proved to be a struggle for many immigrants. Kessler’s grandparents decided they would be happier back in Europe, even buying passage on a ship so they could return to their homeland. But World War I broke out, canceling their trip.

“The harbormaster told my grandparents to hold their tickets until after the war, and if you want to go back, we’ll redeem them,” Kessler says. “Thank God, they didn’t go back.”

By 1914, declining economic conditions and a surge in nativism and xenophobia – a forerunner of today’s anti-immigration climate – brought an end to the Galveston Movement. Still, the program resulted in an estimated 10,000 persecuted Jews finding new homes in the American hinterland in places few had imagined.

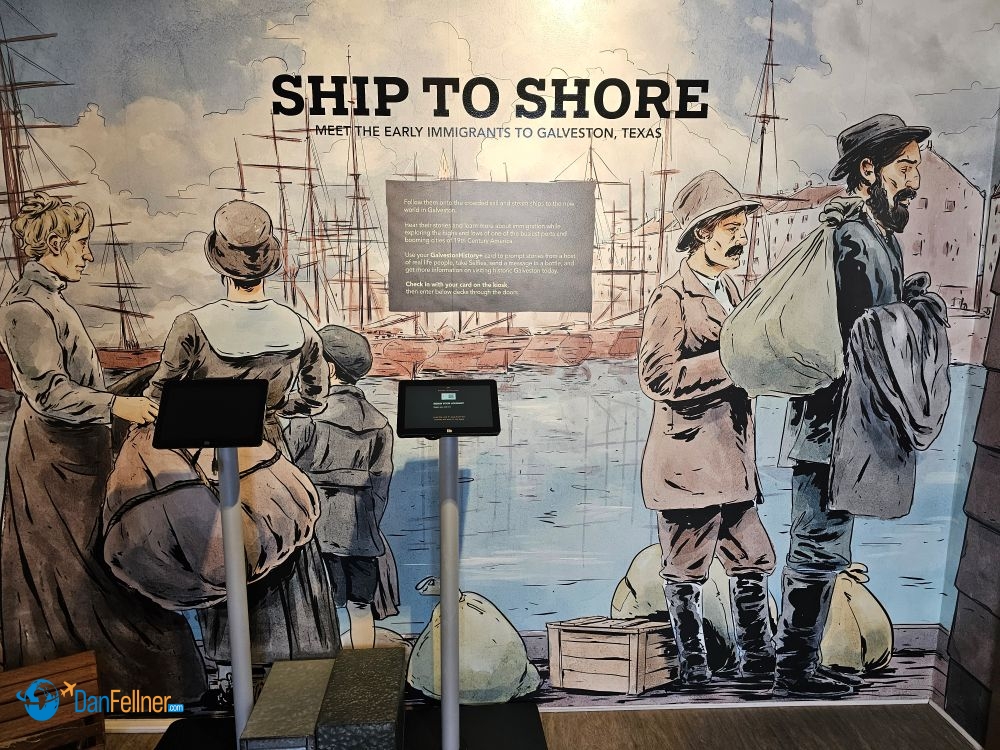

The Galveston Historic Seaport Museum chronicles the immigrant experience in an interactive exhibit called “Ship to Shore.”

The Galveston Historic Seaport Museum chronicles the immigrant experience in an interactive exhibit called “Ship to Shore.” The exhibit includes a prominent photo of Henry Cohen. Computer terminals enable visitors to search for information taken from ships’ passenger manifests pertaining to their ancestors’ arrival in Texas. The Galveston County Museum, located inside the county courthouse, also features artifacts related to the Galveston Movement.

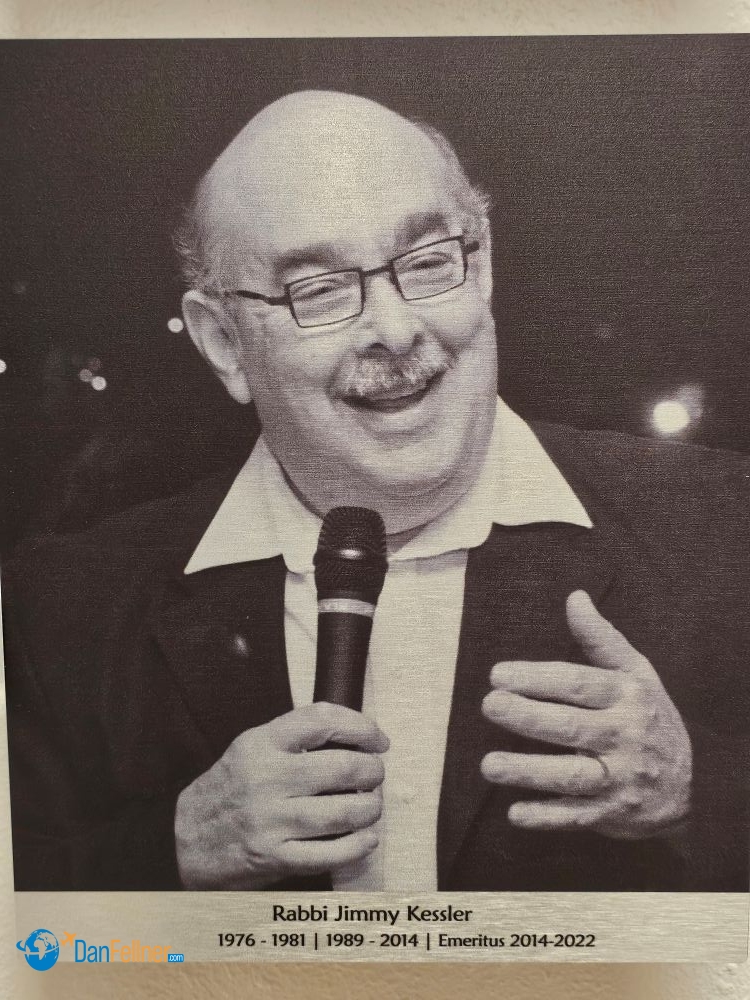

Kessler’s late husband Jimmy, who died in 2022, was another key figure in Galveston’s Jewish history. Jimmy Kessler served as B’nai Israel’s rabbi for 32 years until his retirement in 2014. He also was the founder and first president of the Texas Jewish Historical Society, which is now 45-years-old and has more than 1,000 members.

Rabbi Jimmy Kessler, who led Galveston’s Congregation B’nai Israel for 32 years. Kessler was the founder of the Texas Jewish Historical Society and has written extensively about the Galveston Movement.

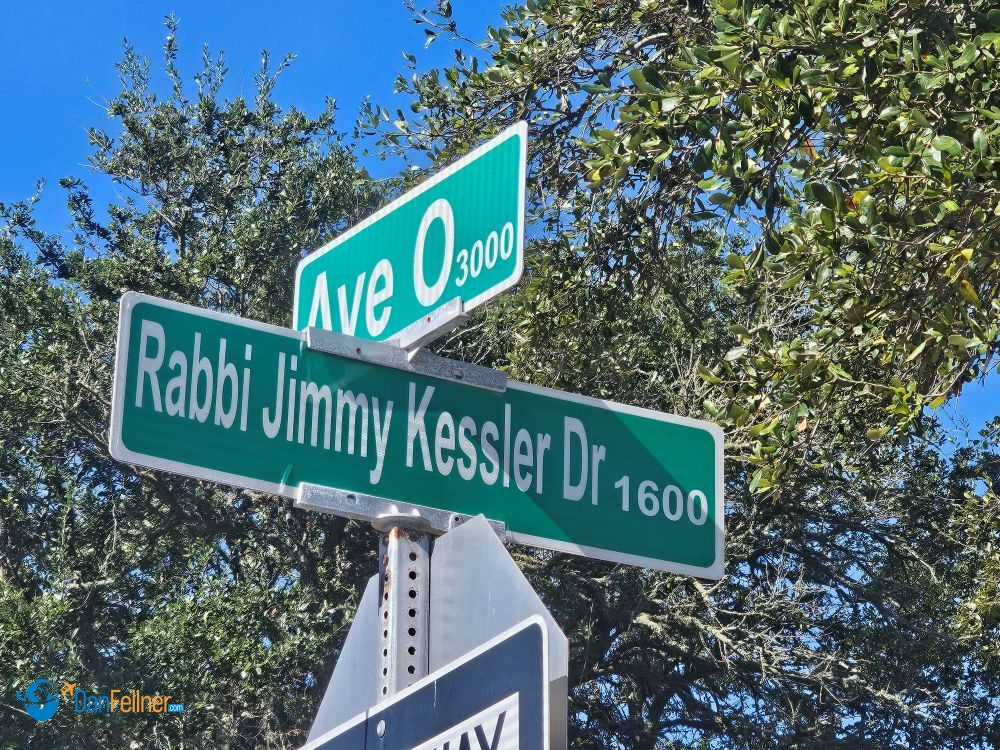

Jimmy Kessler was devoted to telling the story of the Galveston Movement, writing three books about the area’s Jewish history, including a biography of Henry Cohen – The Life of a Frontier Rabbi. The street on which B’nai Israel is located was renamed Jimmy Kessler Drive in 2018, honoring his service to the congregation and the greater Galveston community.

“I’m married to a street,” jokes Shelley Kessler, adding that “Jimmy, with what he did to preserve Texas Jewish history, kept all of this (the Galveston Movement) in the forefront.”

The street on which B’nai Israel is located in Galveston was renamed Jimmy Kessler Drive in 2018, honoring the rabbi’s 32 years of service to the congregation and the greater Galveston community.

B’nai Israel, which now has a membership of 125 families, relocated to a new building in 1955, named the Henry Cohen Memorial Temple.

The congregation’s original synagogue – built in 1870 – was the spiritual launching point for the Jewish immigrants who were part of the Galveston Movement. It still stands on Kempner Street (named after a prominent Jewish family that included Mayor Isaac Kempner) in downtown Galveston. The building is now a private residence. Galveston also has a small Conservative shul, Congregation Beth Jacob, that was founded in 1931.

Robert Goldhirsh, 75, former president of Congregation B’nai Israel and another descendant of immigrants from the Galveston Movement, has been the caretaker of the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery for the past three decades. Several hundred Jews – some of whom came to America in the Galveston Movement — are buried in the cemetery. Henry Cohen also is interred there.

Robert Goldhirsh, former president of Congregation B’nai Israel and a descendant of immigrants from the Galveston Movement, has been the caretaker of the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery for the past 35 years.

Both Goldhirsh and Kessler say that despite perceptions of deep-rooted intolerance in Texas, they’ve encountered little to no antisemitism in Galveston.

“Most of the people I know, it makes no difference that I’m Jewish,” Goldhirsh says. “We’re just Galvestonians.”

The gravesite of Rabbi Henry Cohen, one of the founders of the Galveston Movement. Cohen and his family are buried in Galveston’s Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery, along with several hundred other Jews.

Indeed, Goldhirsh says the biggest threat to Jewish life on the island comes from Mother Nature. With climate change a contributing factor, recent years have seen a significant rise in weather-related disasters in Texas. For instance, Hurricane Ike in 2008 led to widespread flooding on Galveston Island and caused water damage in both synagogues.

“During one of the High Holiday services, there was a hurricane headed this way and we had to cancel for fear that the congregants would be caught in a bad storm,” he recalls. “You have to listen to the weather reports. If they say ‘leave,’ you better leave.”

© 2025 Dan Fellner

4 Comments

Bill Asher

My grandparents on my mothers side were part of the Galveston Movement. My mother and her two brothers were BOI. Joe and Bella Orloff arrived in 1912 and the first child was born in 1913. My mother was born in 1919 on Q 1/2 street by a midwife. Eventually they moved to Houston were my mother grew up in a two story home on Wichita and Dowling (‘Jewish Houston’).

Dan Fellner

Thanks for the comment, Bill. I’ve heard from a lot of people who are descendants of immigrants who arrived in the Galveston Movement.

Dennis Halpin

Great article! I am a descendent of the Galveston Plan. My father’s mother and her family arrived in Galveston in 1913. Her father, my great-grandfather, left Russia first and arrived in Baltimore. There, a person named Louis Halfant told him to go to Galveston, which he did. He wrote the rest of the family to join them there. My grandmother told me about the route, and as you wrote, she and the rest of her family (my great-grandmother, her brothers, and some cousins), went from Russia by train to Bremen, Germany, there boarding a boat for Galveston. There she met a Jewish soldier at Fort Crockett, Abraham Halpin, and they were married in 1916. My father, Morris, was born on the island in 1918. My father’s family left Galveston for Houston in the mid 1930s when dad was in high school. I was born here in Houston. The last of my family who were still in Galveston left for hurricane Ike in 2008 and I no longer have any family there.

Dan Fellner

Thanks for sharing your family’s story, Dennis. Such a fascinating history!

Comments are Closed.