Exploring the city’s inspiring Jewish history during a brief visit

Aish.com/Arizona Jewish Life Magazine — April 2018

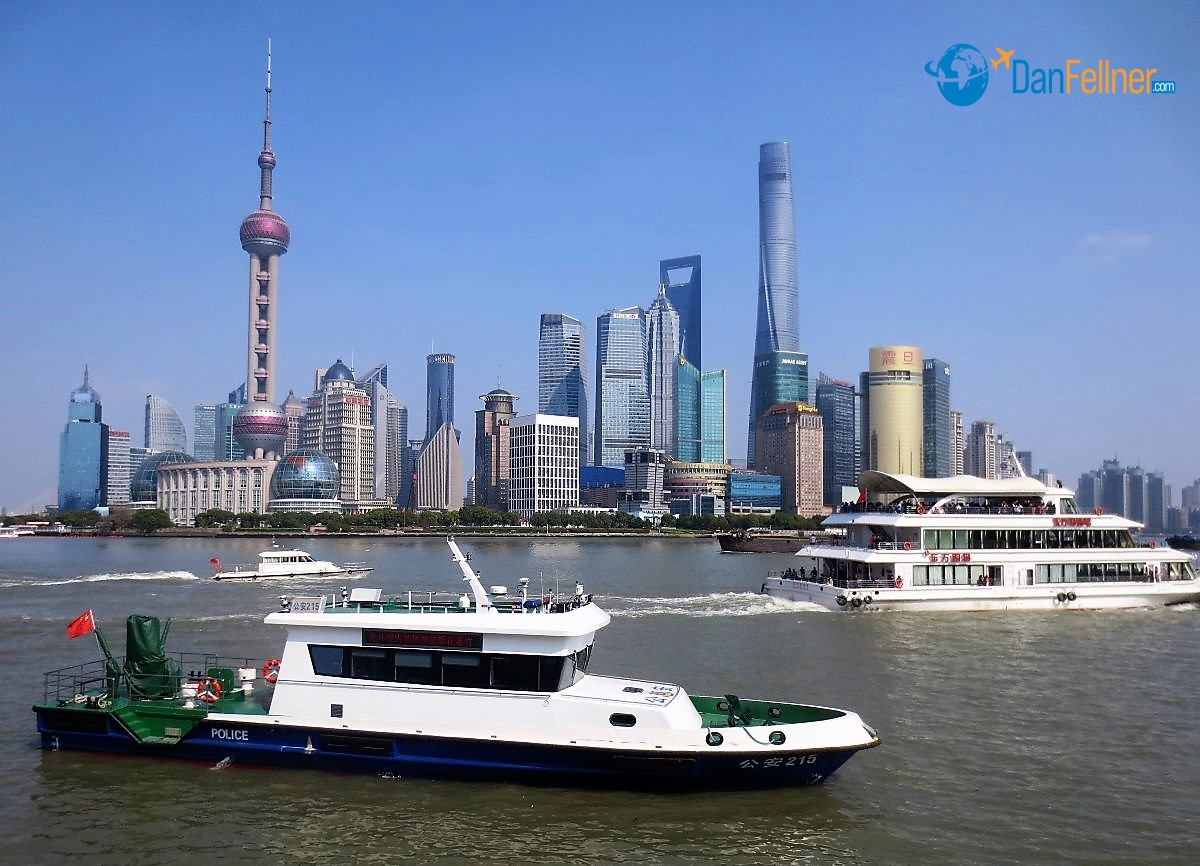

SHANGHAI — China’s largest city of 23 million people features one of the most dazzling skylines in the world, a booming economy and a compelling mixture of Eastern and Western cultures.

But not many people are aware that Shanghai also offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into the history of one the most unique Jewish communities in the Far East. As a city that accepted about 20,000 Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust in Europe, Shanghai became known at the time as a “Noah’s Ark” for Jews who had no other place to go.

Dvir Bar-Gal leads a “Tour of Jewish Shanghai” in front of the city’s dazzling skyline.

With only 24 hours to explore the city at the conclusion of a 14-day Asian cruise on the Holland America Volendam, I opted to take a half-day “Tour of Jewish Shanghai.” It was led by Dvir Bar-Gal, an Israeli-born journalist who has lived in Shanghai for the past 17 years.

With a style that was part history professor, part standup-comedian, Dvir taught our group of 15 tourists – mostly Americans – all about Shanghai’s Jewish past and took us to the sites that helped bring to life a Jewish community that once thrived here.

It took me just a 20-minute walk from where the Volendam was docked to join the tour. Appropriately, we met at the Fairmont Peace Hotel, which was built by Sephardic Jews from Bagdad, who were part of the first wave of Jewish immigrants to Shanghai in the late 19th century. This group included two prominent families – the Sassoons and Kadoories.

A monument at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

“People came here with nothing and created an economic empire in the Far East,” noted Dvir about the Baghdadi immigrants.

A second wave of Jews arrived in the 1920s, Ashkenazim fleeing pogroms and revolutions in Russia.

From the Fairmont, our group walked one block to The Bund, Shanghai’s pedestrian riverfront with a spectacular view across the Huangpu River to the city’s enormous skyscrapers. It was at The Bund where Dvir told us about the third – and most famous – wave of Jewish immigrants.

From 1933 to 1941, Shanghai accepted about 20,000 Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust. Most came from Germany and Austria, which had stripped Jews of their citizenship and encouraged exile before turning genocidal. Outside of the Dominican Republic, Shanghai was the only place that allowed Jews to enter as it did not require a visa. In fact, by 1939 more European Jews had taken refuge in Shanghai than in any other city in the world. (The Dominican Republic was the only sovereign country that granted visas to large number of Jewish refugees, most of whom settled in Sosua, an agricultural colony on the Dominican Republic’s northern coast — https://danfellner.com/2023/04/30/sosua-jews/)

The Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum was opened by the Chinese government in 2007.

Why did China offer Jews a safe-haven from the Nazis when so many other countries turned their backs? Dvir says it wasn’t a conscious decision by the Chinese government. In fact, Shanghai at the time was an international city not completely under Chinese control. Several foreign powers, including the United States, France and the United Kingdom, claimed portions of the city and a visa was not required to enter Shanghai until August 1939.

Still, Dvir says once the Jews arrived, they were treated well by the Chinese, who have long been known for their lack of anti-Semitism. Dvir believes there are many reasons for this, including that the Chinese identify with Jewish suffering, relate to their status as an underdog and were “oppressed themselves by foreign powers.”

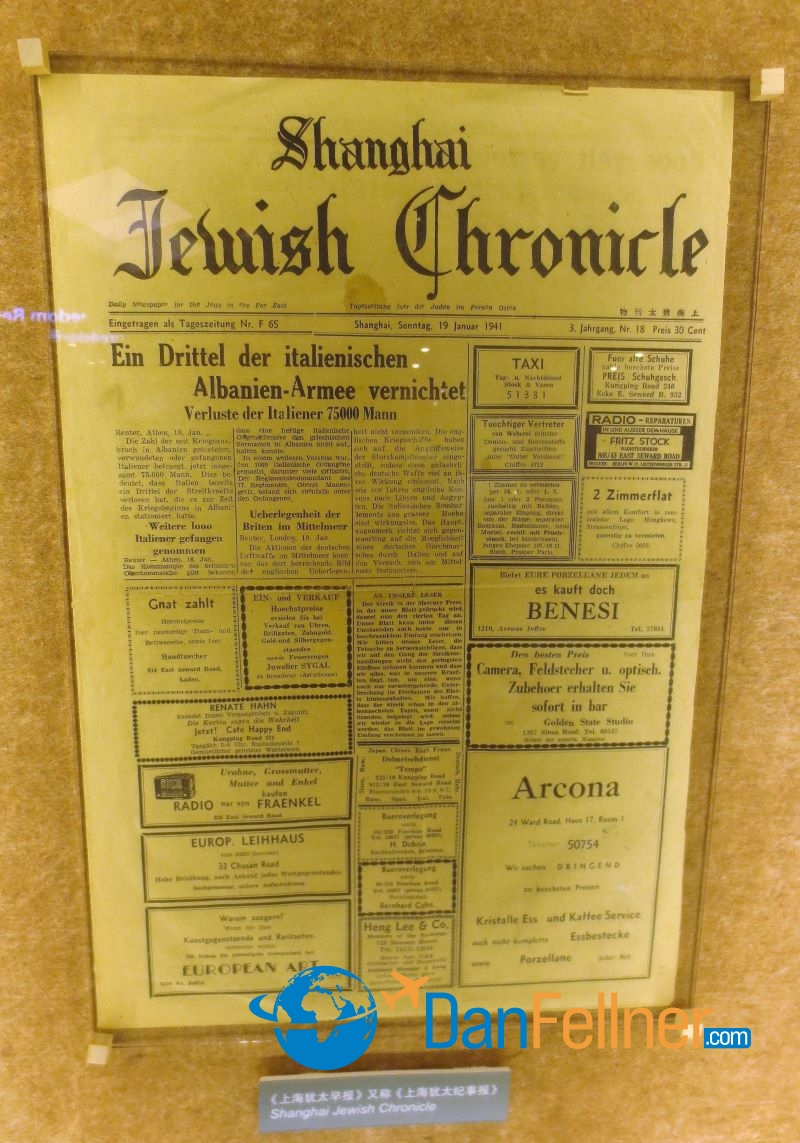

Jewish life in Shanghai prospered during the 1930s. At one time, there were six working synagogues and about 10 Jewish newspapers. Jews lived harmoniously with the Chinese in a section of town called the Hongkou District, which was dubbed “Little Vienna” because so many Austrian Jews lived there.

The renovated Ohel Moshe Synagogue, built by Russian Jews in the 1920s, is housed inside the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

The final group of Jewish refugees to arrive in Shanghai included about 300 Polish Jews from the famous Mir Yeshiva, which ultimately became the only European yeshiva to emerge from World War II intact. The Jews from Mir Yeshiva first escaped in 1939 from Poland to Lithuania, where they received transit visas from the Japanese consulate general in Kovno, Chiune Sugihara.

A Jewish newspaper from 1941 on display at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Shanghai, which ended the flow of foreign funds to the Jewish refugees, who were becoming increasingly impoverished. The Japanese also imposed restrictions on where Jews could live, creating a “Designated Area for Stateless Refugees,” better known as the Shanghai Ghetto.

Conditions in the ghetto were difficult but a vast majority of Shanghai’s Jews survived the Holocaust. Most emigrated to Israel, the United States, Australia and Hong Kong after the Communists took control of the government in 1949.

Dvir drove us by van to the city’s Hongkou District where we walked through narrow streets and parks lined with blooming cherry-blossom trees to explore the traces of what once had been bustling Jewish life in the area.

Blooming cherry blossoms in Shanghai’s Hongkou District, which was the center of Jewish life during the 1940s.

The highlight was a visit to the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum on Changyang Road, which contains exhibits, monuments and an exhibition hall in which more than 140 photos are displayed with a multi-screen projection system. Dvir served as an adviser to the Chinese government when it opened the museum in 2007.

The museum also houses the former Ohel Moshe Synagogue, built by Russian Jews in the 1920s. It later became the hub of Jewish life when the community was ghettoized in the 1940s. After the war, the synagogue was confiscated by the Communists and converted into a psychiatric hospital. It reopened in the 1990s and was later restored to its original architectural style in 2007. The building has been inscribed on the list of architectural heritage treasures of Shanghai.

Exhibit at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum commemorating the 1993 visit of Yitzhak Rabin, the former Israeli prime minister.

Ohel Moshe is not used for religious services and the city has only has only one other remaining synagogue – Ohel Rachel. The largest synagogue in the Far East, Ohel Rachel was built by the Sassoon family in 1920. But it currently does not host services on a regular basis and is not open to visitors.

With no functioning stand-alone synagogues, Shanghai’s current population of about 4,000 Jews have a choice of praying at one of three Chabad branches or in private venues.

The tour also included a visit to a home where Jewish refugees once lived and the former site of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which provided immense financial support to Shanghai’s Jewish refugees during their years of hardship.

Dvir says about 3,000 tourists take his tour every year, a majority of whom are Americans. He adds that before their arrival, many had no idea about the city’s rich and inspiring Jewish history.

“Some people have some knowledge about Jewish life here, but it is vague,” he says. “It comes to life when they take this tour.”

After the tour was over, I had a few hours left to enjoy Shanghai before I needed to return to the Volendam. I chose to see a Chinese acrobat performance at a downtown theater, where I watched an amazing array of gymnasts, jugglers and motorcyclists who speedily whirled their vehicles inside a cage.

A Chinese acrobat show performed at a Shanghai theater.

Back on the ship at 10 p.m., I took one last look at the city’s wondrous skyline – lit up like a pinball machine – and reflected on what I had learned during my 24 hours in this crowded and frenetic city.

Perhaps an exhibit at the Jewish Refugees Museum best sums up what a Holocaust historian has called “the miracle of Shanghai.”

In 1993, Yitzhak Rabin, the former Israeli prime minister, visited the site and inscribed the following: “To the people of Shanghai for unique humanitarian act of saving thousands of Jews during the Second World War, thanks in the name of the government of Israel.”

©2018 Dan Fellner