I’m all shook up in Tupelo!

Aish.com/Arizona Jewish Life Magazine — July 2018

TUPELO, Miss. — Inside a museum next to the modest two-room house where Elvis Presley was born in 1935, visitors will find all the things you’d expect to see in a shrine celebrating the early years of a boy who would grow up to become the King of Rock ‘N’ Roll.

The modest two-room house where Elvis was born in Tupelo in 1935.

There are guitars, childhood photographs, old record albums, performance costumes and other memorabilia from Elvis’ illustrious career.

But amidst all the artifacts inside the Elvis Presley Museum, there’s something else that one wouldn’t expect to find – a gold-colored chrome menorah with nine Hanukkah candles.

Could it be that perhaps the greatest American cultural icon of the 20th century was a member of the tribe?

Well, sort of.

Turns out, Elvis’ maternal great-great grandmother, Nancy Burdine, was believed to be Jewish. Her daughter gave birth to Doll Mansell, who gave birth to Elvis’ mother, Gladys Smith. That, according to a Jewish law called halakha, which confers Jewish lineage by way of the mother, makes Elvis technically a Jew.

Elvis Presley’s Chanukah menorah on display at the Elvis Presley Birthplace Museum in Tupelo, Miss.

While Presley was aware – and even proud — of his Jewish pedigree, there is no evidence he ever practiced the faith.

I recently went to Tupelo, Miss., to learn more about Elvis’ upbringing and his Jewish roots. In the process, I gained a new appreciation for Judaism in the Bible Belt and the resoluteness of a small – but close-knit — Jewish congregation in the hills of northeast Mississippi that has survived for more than 70 years.

A statue of Elvis in downtown Tupelo.

As for the menorah, it was originally owned by the family of George Copen, who moved to Tupelo from New York in 1953. I met Copen, now 75, at Friday night Shabbat services at Temple B’Nai Israel, a small Reform synagogue located in a quiet residential neighborhood about a 10-minute drive from Elvis’ birthplace.

Copen told me that his childhood best friend in Tupelo was a boy who lived across the street named Jim Hill. Jim’s mother, Janelle McComb, was a close family friend of the Presleys. She first met Elvis when he was just a two-year-old, beginning a friendship that would last until Presley died in 1977 at his Graceland mansion in Memphis.

According to Copen, Janelle once asked to borrow his family’s menorah and show it to some friends. Apparently, Elvis was one of those friends. At any rate, the menorah was never returned to the Copen family. George speculates that Janelle gave the menorah to Elvis; he later became aware of a photo of Elvis with the menorah. Perhaps The King viewed it as a “good luck charm,” the name of one of his biggest hits.

Temple B’Nai Israel, Tupelo’s small Reform synagogue.

“I was pretty upset with Janelle when I realized she might have given it to Elvis,” says Copen. “Even after the funeral (McComb died in 2005) I looked throughout her house, but no menorah. Gone.”

But later, George heard that the family menorah had been found and was on display at the Elvis Presley Birthplace Museum. Indeed, much of the museum’s collection consists of gifts and mementos that Elvis had given Janelle over the years, which she donated to the museum.

Marc Perler leads Shabbat services at Tupelo’s Temple B’Nai Israel.

So that’s where the Copen family menorah sits today, on display for the museum’s 50,000-100,000 annual visitors to view.

Copen says he’s honored that so many people have the chance to see a family heirloom, which he believes sends an important message of tolerance that Elvis embraced.

“Janelle wanted to show that Elvis liked all faiths,” says Copen. “I would rather people see the menorah there at the museum than at my house. Maybe this will help everybody appreciate each other and say, ‘I’m not just a Christian, or Jewish, or a Buddhist. We are all one people.’”

Elvis (far right) with two of the Fruchter children in Memphis in the early 1950s (photo courtesy of Harold Fruchter).

Elvis was 13 when he and his parents left Tupelo for Memphis. There, the Presleys lived downstairs from the family of Rabbi Alfred Fruchter of Beth El Emeth Congregation. The rabbi’s son, Harold, now 65 and living in Maryland, told me the two families became good friends; Harold’s mother would often have coffee with Elvis’ mother Gladys.

In 1954, Elvis recorded his first hit record, “That’s All Right,” at Memphis’ Sun Record Company. But the Presleys didn’t own a record-player. Harold says Elvis borrowed the Fruchter’s record-player so he could play the song for his parents.

At one point, Elvis worked off-and-on for Rabbi Fruchter as a “Shabbos Goy,” meaning he would perform certain types of work that religious law prohibits Jews from doing on the Sabbath, like turning lights on and off.

“My parents never had even an inkling that Elvis may have been Jewish,” says Harold. “If they would, they would never have considered asking him to be a ‘Shabbos goy.’”

When Elvis’ mother Gladys died in 1958, he made sure to put a star of David on her headstone at a Memphis cemetery, in honor of his Jewish heritage. After Elvis died, Gladys was reinterred at Graceland. Her new gravestone, lacking Elvis’ attention, didn’t get a star.

The star of David on Gladys Presley’s grave, honoring her Jewish heritage. The grave is now on public display at Graceland in Memphis after being in storage for 40 years.

Toward the end of his career, there are photos of Elvis wearing a chai pendant during concert performances. In fact, he was reportedly wearing both a chai and a cross the night he died. In Memphis, he belonged to the Jewish Community Center and gave money to several Jewish organizations, including $150,000 to the Memphis Hebrew Academy.

“He was very close to the Jewish people, especially in Memphis,” says Copen. “He always treated them very nicely and they treated him very nicely.”

It’s believed that “Colonel” Tom Parker, Elvis’ Dutch-born manager, didn’t want his client’s Jewish roots to become public knowledge, thinking it might be seen as a negative by some of the hordes of Elvis fans in the Bible Belt back in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Elvis wore this chai necklace — now kept in storage at Graceland in Memphis — during concert performances in the final years of his life.

Following Shabbat services at Tupelo’s B’Nai Israel, I sat down with Marc Perler, 73, the synagogue’s lay leader (the temple doesn’t have a full-time rabbi), to learn more about Jewish life in the Deep South. B’Nai Israel has a membership of only about 20 families, a number that has steadily declined over the years.

“We’re ageing out,” says Perler. “We don’t have that many young people. It’s the same in small towns everywhere.”

Still, Perler says the town of 38,000 people has been hospitable to its Jewish residents. When the congregation’s first permanent structure was built in 1957, Perler says a number of Tupelo’s non-Jews donated money because they “thought it was important that Tupelo had a broad cross-section of people living here.”

As shown on this plaque at Graceland, Elvis belonged to the Jewish Community Center in Memphis and gave money to several Jewish organizations.

And when a tornado destroyed a nearby Methodist church in 2014, Perler says B’Nai Israel – without hesitation — loaned out their facility so that their Christian neighbors would have a place to hold Sunday school.

“It was the right thing to do,” he says. “I’d like to think they would do the same for us.” He adds that despite the congregation’s attrition, “we’ve had no trouble being Jewish in small-town Mississippi.”

As for Tupelo’s favorite son, Perler recounts the story when he once met Elvis in Nashville at a recording studio in the early 1960s. He says he was surprised when he later learned of Presley’s Jewish background.

“I thought it was cool,” he says. “It was like, ‘welcome to the club.’”

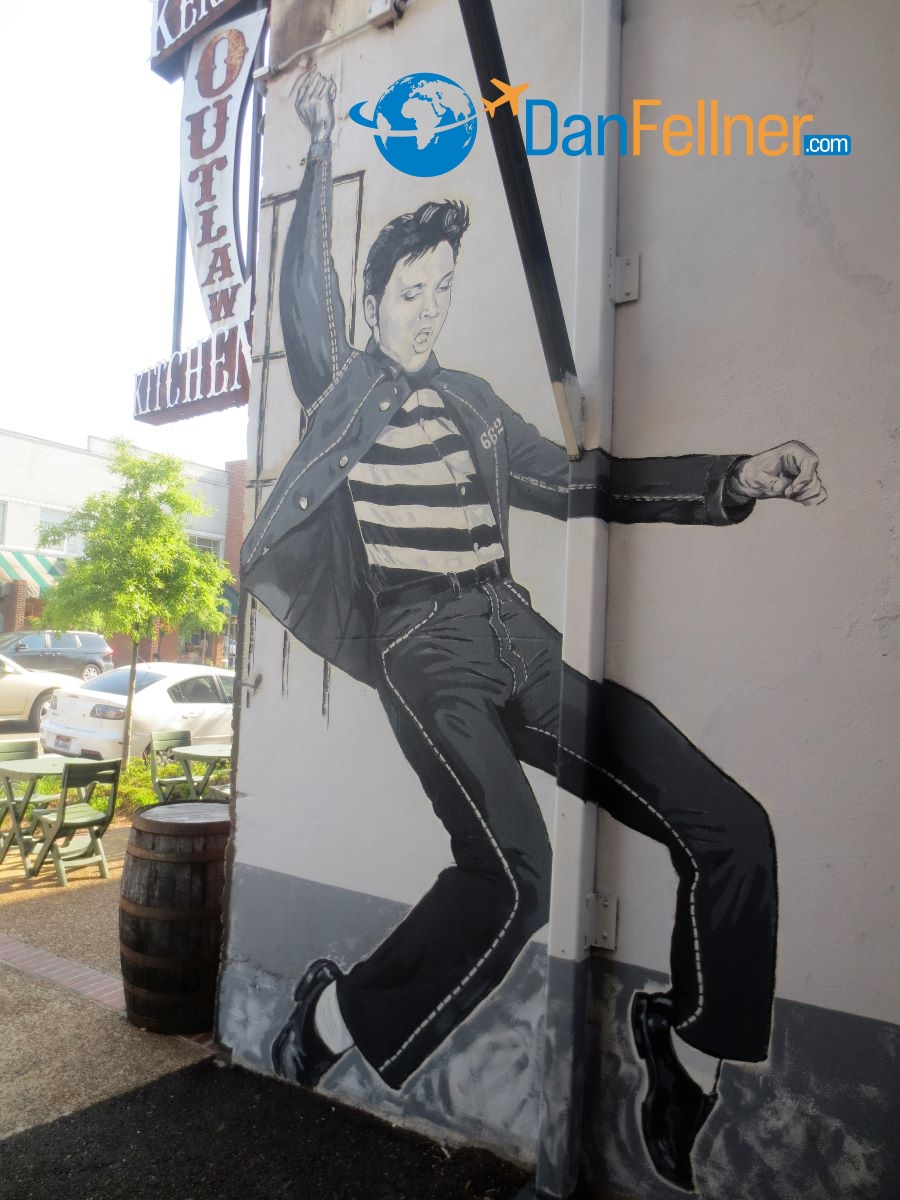

A street mural of Elvis Presley in downtown Tupelo.

© 2018 Dan Fellner