Tourists to Serbia’s White City will encounter vibrant nightlife, a reemergent cultural scene and the unmistakable sense of walking through modern history.

Hadassah magazine – April/May, 2010

Scattered throughout downtown Belgrade are the eerie, ghost-like shells of several former government buildings. These casualties of a 1999 NATO bombing campaign that ultimately led to the withdrawal of Serbian troops from Kosovo are grim reminders of the conflict that has engulfed the Balkans since the breakup of Yugoslavia into seven different countries.

Remnants of NATO’s 1999 bombing campaign in downtown Belgrade.

But tensions in the region have cooled considerably during the past 10 years, and Serbia is no longer viewed as a political pariah. There is even talk of joining the European Union. And Belgrade, its capital and largest city with about 1.5 million residents, is reemerging as a tourist destination, known for its vibrant nightlife and café culture.

The center of it all is Knez Mihailova Street, a pedestrian promenade that evokes comparisons to Barcelona’s La Rambla. Belgrade’s version is packed with outdoor cafés, street performers, souvenir stands and boutiques, and is adorned with a number of century-old neo-Renaissance and Art Nouveau buildings.

Knez Mihailova leads into Belgrade’s most prominent landmark, the Kalemegdan Citadel, an often-rebuilt fortress dating to Roman times that overlooks the confluence of the Danube and Sava Rivers.

Serbian flags for sale on busy Knez Mihailova Street in Belgrade.

Belgrade’s small but active Jewish community boasts both Sefardic and Ashkenazic influences. And beyond the city, in the northern part of Serbia, tourists can visit two of Eastern Europe’s most architecturally splendid synagogues.

History

From the time they first arrived in the 10th century until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire some 900 years later, Jews fared better in Belgrade — which means White City in English — than in many other East European capitals.

The city became a refuge for Ladino-speaking Sefardic Jews fleeing the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions. They settled in the Dorcol region, close to the Danube. Ashkenazic Jews arrived from Austria-Hungary and Central Europe and lived further south, near the Sava River.

Entrance to Belgrade’s Kalemegdan Citadel.

Jews were involved in trade between the Ottoman Empire’s northern and southern provinces, becoming especially important in the salt trade. In the mid-17th century, Belgrade’s yeshiva became widely known and the community flourished.

In the years following independence from the Turks in 1830, Jewish fortunes in Belgrade waxed and waned under different rulers, some of whom implemented laws favoring non-Jewish merchants and barring Jews from certain professions. In the 20th century, Jews fought alongside Serbs in the 1912 to 1913 Balkan Wars and in World War I.

When the Germans occupied Belgrade in April 1941, about 12,000 Jews lived in the city – most of them Sefardim. Only 13 months later, Belgrade suffered the infamy of being the first city in Europe declared Judenfrei. At least 2,000 Jews were killed by firing squads at the Topovske Supe transit camp in central Belgrade; most of the rest were gassed at Sajmiste, a camp near the Sava River that had formerly been a fairground. Only about 2,000 of the city’s Jews survived the Holocaust.

Site of the Sajmiste concentration camp near the Sava River in Belgrade.

After the war, Jews experienced less anti-Semitism in Yugoslavia than in many other Communist states. Still, many left the country for Israel or the United States.

Community

There are now about 3,000 Jews remaining in Serbia, two-thirds of whom live in Belgrade and its suburbs. Social service programs, funded largely by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, are administered through an umbrella organization called SAVEZ, the Federation of Jewish Communities in Serbia (www.savezscg.org).

The Kosmajska Temple, Belgrade’s only functioning synagogue.

SAVEZ and the Jewish Community of Belgrade (Kralja Petra 71a; www.jobeograd.org; 011-381-11-2624-289) are housed in a building that was designed in 1928 for the Sephardic community. It sits on a hilly street in the old section of Belgrade, two blocks northeast of Knez Mihailova. The building is also home to the Jewish Historical Museum and a children’s theater.

About a 10-minute walk from the community center is Belgrade’s only functioning synagogue, at Marsala Birjuzova 19. Known as the Kosmajska Temple because the street was called Kosmajska before World War II, the synagogue was opened in 1926 by Ashkenazim, although today most of its congregants are Sefardim. Rather than destroy it, the Nazis used it as a brothel.

Inside Belgrade’s Kosmajska Temple.

The synagogue is under the supervision of Serbia’s only rabbi, Yitzhak Asiel. It is set in a large, gated courtyard in a gray, neo-Classical-style building topped with a round window bearing the Star of David. Housed in the same complex are a youth center, social hall, Jewish kindergarten, a small medical clinic and a kosher kitchen. Meals can be prepared for visitors; contact Vesna Kovacevic (olga.gabaj@gmail.com; 011-381-11-3036-156).

Belgrade’s Jewish community is perhaps best known to outsiders for its Baruh Brothers Choir. Founded in 1879 as the Serbian-Jewish Singing Society, the coed choir regularly performs in Serbian music festivals, has appeared on television and radio, recorded albums of traditional Jewish music and even performed in New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Aleksandar Necak, president of Serbia’s Jewish Community.

Serbia is lagging behind other East European countries in making restitution for Jewish property nationalized by the Communists. To get permission to leave the country in 1948, about 3,000 Jews were forced to give up their land. Jewish leaders have launched a letter-writing campaign pressing government officials to pass a law appropriating compensation. Community President Aleksandar Necak calls it his organization’s “absolute, number-one priority.”

Sights

A good starting point is the Jewish Historical Museum (www.jimbeograd.org; 381-11-2622-634), located on the first floor of the community center. Established in 1948, the museum chronicles the history of Jews throughout former Yugoslavia and features an impressive collection of Judaica, including a 17th century Megilat Esther from Portugal.

The Jewish Historical Museum offers an impressive collection of Judaica.

For genealogists, the museum also has a database of birth, marriage and death records of Belgrade’s Jews from the middle of the 19th century until 1941.

From the community center, a short walk downhill toward the Danube River leads right into what once was the Jewish quarter in Dorcol. Its nucleus, Jevresjka (Jewish) Street, still exists as does the building that once housed the Jewish societies Oneg Shabat and Gemilut Hasadim. The façade of the yellow-and-pink building (16 Jevresjka), now the Cinema Rex theater, is inscribed with Psalm 71 in both Hebrew and Serbian above two large Stars of David.

The Burning Menora holocaust memorial overlooks the Danube River.

Also in Dorcol, overlooking the Danube, is the powerful Holocaust memorial Burning Menora, dedicated in 1990. It was designed by sculptor Nandor Glid, a Holocaust survivor who was born in Yugoslavia. Glid also created monuments for Yad Vashem and the Dachau concentration camp.

Across the Sava River from the bus and train stations in a part of town now called New Belgrade are the remnants of the Sajmiste Concentration Camp, where about 8,000 Jews – mostly women and children — were murdered in mobile gas chambers. The camp’s guard tower and a portion of the barracks are still standing. In the mid 1990s, a large memorial was erected on the Sava riverbank in memory of Sajmiste’s 40,000 victims, which also included Serbs and Roma.

The Jewish cemetery (1 Mije Kovacevica), about a 10-minute drive east of the town center, contains another Holocaust memorial. The monument, a menora in front of two large stone tablets, was erected in 1952 by the Yugoslavian government with support from the Jewish community. The cemetery is also home to an impressive monument dedicated to Jewish soldiers killed in the 1912-13 Balkan Wars and World War I.

A Holocaust memorial at the Jewish cemetery, about a 10-minute drive from the Belgrade city center.

Zemun, a Belgrade suburb across the Danube, was the southern outpost of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at a time when the Turks ruled Belgrade. Today, it is a charming town of about 150,000 residents with a number of historic buildings, cobblestone streets and spectacular views of Belgrade across the river.

In 1850, an Ashkenazic synagogue (Rabin Alcalaj Street 5) was built in Zemun that still stands, although it is now owned by the city and currently houses a restaurant serving traditional Serbian dishes. The Jewish Community of Zemun (Dubrovacka 21; http://joz.rs/index2_en.html), located around the corner from the synagogue, is trying to raise funds to buy it back.

Other Sights

The tomb of Josip Broz Tito in Belgrade.

For those fascinated by Josip Broz Tito — the man who held multiethnic Yugoslavia together for 35 years — the place to go is the Yugoslav History Museum (Boticeva 6). The museum, which consists of three buildings in a park-like setting, has a collection of more than 200,000 items relating to the country’s history in the 20th century, with a main emphasis on the life and work of Tito. Between his two marriages, Tito had a relationship in the 1940s with Hertha Haas, a woman of Jewish descent who bore him a son, Aleksandar Miso Broz, today a Croatian diplomat.

Tito’s tomb is on display in the House of Flowers, along with collections of his office furniture, uniforms and ceremonial batons. The museum is a 15-minute drive southeast of the town center and is easily accessible by trolley.

Side Trips

The gorgeous old synagogues in Subotica and Novi Sad in Serbia’s northern province of Vojvodina are must-sees for Jewish travelers who can get away from Belgrade for a full day. Vojvodina, which was part of Hungary before World War I, had active Jewish communities in several dozen towns in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

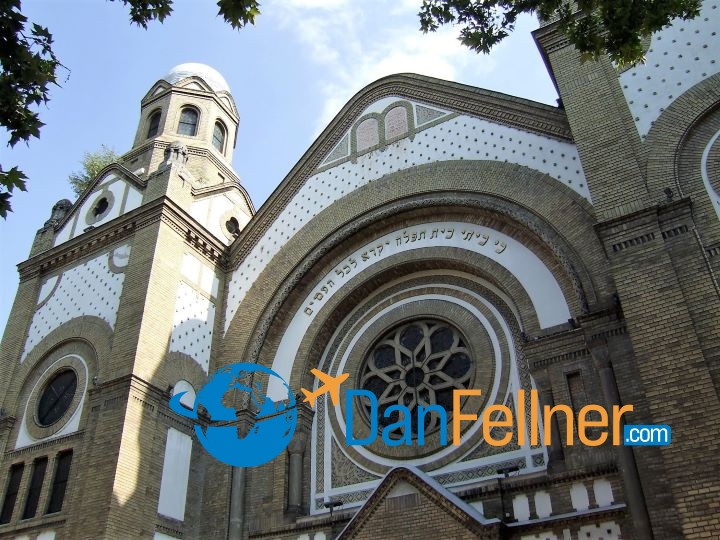

Subotica’s magnificent synagogue in northern Serbia is considered one of the finest examples of Art Nouveau architecture in Europe.

From Belgrade, it is a two-hour drive to Subotica, only six miles from the Hungarian border. Near the town center is its magnificent synagogue, built in 1902 and considered one of the finest surviving examples of Art Nouveau architecture in Europe.

The main entrance is on Jakab and Komor Street, named after the Hungarian-Jewish architects who designed both the synagogue and Subotica’s Town Hall. The house of worship has five green-and-yellow-tiled domes, each topped with a Star of David, and the inside is resplendent with wall murals, inspired by folk art, and numerous stained-glass windows.

The Subotica synagogue has five green-and-yellow-tiled domes, each topped with a Star of David.

In its heyday, the synagogue held 1,500 worshippers. But it fell into disrepair after World War II and was last used for religious services in the late 1940s. Renovations began in 1980; however, much work remains. The Subotica Jewish Community (jewcom@nadlanu.com) is raising funds for the restoration along with the municipal government, which currently owns the building.

Next door, at Ulica Dimitrija Tucovica 13, are the headquarters for the Jewish community and a small working synagogue for the city’s 250 Jews. There is no rabbi but weekly Shabbat services are led by a hazzan.

The town square of Novi Sad, Serbia’s second-largest city.

Novi Sad, about halfway between Subotica and Belgrade, is the capital of Vojvodina and Serbia’s second-largest city. Its synagogue, at Jevresjska 9, was designed by Lipot Baumhorn, another Hungarian-Jewish architect. It opened in 1909 a few blocks from Novi Sad’s main town square, the fifth synagogue to be built on that spot.

The synagogue was constructed in a neo-Classical style with dark yellow bricks. The façade, flanked by two towers, is inscribed in large Hebrew letters: “This is the house of worship for all nations.” Inside, the sanctuary has several stunning stained-glass windows. Most of the Jews in Novi Sad who survived the Holocaust immigrated to Israel; in 1991, the synagogue was turned over to the city. It is now used as a concert hall.

A stained-glass window in the Novi Sad synagogue.

Personalities

Moshe Pijade, a confidant of Tito’s who rose to the highest echelon of the Yugoslavian government in the 1950s, was born in Belgrade in 1890 to a prominent Sefardic family. In 1925, he was imprisoned for 14 years due to his pro-Communist sympathies. He later fought with the partisans against the Nazis and, in 1954, was elected president of the Yugoslavian Parliament.

Danilo Kis, whose father was a Hungarian Jew, is considered one of the most important Yugoslavian writers of the 20th century. Born in Subotica in 1935, Kis wrote novels, short stories and poetry in Serbo-Croatian. His most famous works, including The Encyclopedia of the Dead (Northwestern University Press) and A Tomb for Boris Davidovich (Dalkey Archive Press), have been translated into English.

Zionist pioneer Theodor Herzl was born in Budapest, but his family originally came from Zemun, and his grandparents are buried in the Jewish cemetery there.

Fishing on the Danube River.

Reading

Jennie Lebel, a Serbian-Israeli historian, provides a comprehensive overview of Jewish life in Belgrade in Until ‘The Final Solution’: The Jews in Belgrade 1521-1942 (Avotaynu). The book, which took Lebel 20 years to research, has been published in English, Serbian and Hebrew.

As a Norwegian journalist, Asne Seierstad covered NATO’s bombing of Belgrade in 1999. She returned a year later to write a book that explores the lives of 13 Serbs, including a politician, rock star, black marketeer and farmer. With Their Backs to the World: Portraits from Serbia (Basic Books) offers interesting insight into the Serbian perspective at a time when the country had few friends.

Perhaps because hostilities have since ebbed and tourists are rediscovering the city, Belgrade in Your Pocket was added to the In Your Pocket lineup of city guides in 2008. The guide provides maps and information on restaurants, events and nightlife. It can be downloaded for free at www.inyourpocket.com/serbia/belgrade and is also available at many Belgrade hotels.

A street performance on Knez Mihailova in Belgrade.

Recommendations

Tour guide Branka Adamovic (brankaguide@yahoo.com; 381-63-712-6692) is knowledgeable about Jewish sights and speaks excellent English. She will drive visitors to the synagogues in Novi Sad and Subotica.

Other than the kitchen in the synagogue, there are no kosher restaurants in Belgrade. But Peking (Vuka Karadzica 2; 381-11-2181-931), Belgrade’s first Chinese restaurant, is a good choice for vegetarian dishes. Peking is on a side street just a block from Knez Mihailova, not far from the Jewish Community building.

The Majestic Hotel (Oblicevvenac 28; www.majestic.rs; 381-11-3285-777) has a great location right off Knez Mihailova, less than a five-minute walk from the synagogue.

Visitors will likely want to spend an hour or two each day experiencing Belgrade’s café culture around Knez Mihailova. There, in the seemingly endless row of bars and restaurants, tourists join the locals drinking espresso or Jelen Pivo, a popular domestic beer. In the evening, Belgraders dress up and promenade en masse – a Balkan pastime called the korso.

Belgrade has been destroyed and rebuilt many times and few historic buildings survive. But the past decade has brought relative calm and, with it, a growing number of tourists who find a culturally dynamic and revitalized city that is leaving the past behind.

The synagogue in Novi Sad is now used as a concert hall.

© 2010 Dan Fellner