A tumultuous past maybe, but the Jews are now on solid ground and Latvia’s repentant capital is one of Europe’s cleanest, safest and most inexpensive destinations.

Hadassah magazine – October, 2003

After a half century of Soviet occupation that dulled its luster and broke its spirit, Riga is on the mend. The city has undergone a stirring revitalization since Latvia regained its independence a dozen years ago. Now, with large, flower-filled parks, an eclectic mix of fascinating architecture and a medieval Old Town that is a labyrinth of narrow cobblestoned streets, Riga is once again becoming worthy of its pre-World War II sobriquet—Paris of the Baltics.

Riga is Latvia’s capital and largest city.

The city also features several sites that chronicle the tumultuous and tragic history of its Jews. Recent years have brought long-awaited government recognition of Latvian culpability in the Holocaust, the construction of Jewish memorials and a modest revival of Riga’s once strong Jewish community.

Perched on the Daugava River about 10 miles inland from the Baltic Sea in northeastern Europe, Riga is Latvia’s capital and largest city, with a population of about 850,000. The city underwent major renovations in 2001 to celebrate its 800-year anniversary and is one of the cleanest, safest and most inexpensive destinations in Europe.

About half of Riga’s residents and a majority of the city’s Jews speak Russian as their first language, a legacy of Soviet times when they came to Latvia from other parts of the Soviet Union. Since breaking free in 1991, Latvia has embraced democracy and a free-market economy. As a result, it has been invited to join both the European Union and NATO in 2004. But westernization has not brought the crowds that flock to other East European cities like Prague and Budapest. Visitors will find plenty of elbowroom to enjoy all that Riga has to offer.

The heart of the city is known as Vecriga, or Old Town, a maze of crooked streets flanked by historic buildings, towering church steeples, cafés and art galleries. Strolling through Old Town is perhaps Riga’s greatest pleasure. Street musicians perform Latvian folksongs, a nice backdrop for the interesting mishmash of Gothic, Baroque, Romanesque and Art Nouveau architecture.

Riga has one of the largest collections of Art Nouveau buildings in the world.

Indeed, Riga boasts one of the largest and best-preserved collections of Art Nouveau buildings in the world. This distinctive German architectural style, also called Jugendstil, dates back about 100 years and features ornately crafted sculptures of flowers, animals, angels, monsters and other odd creatures. Some of Riga’s most stunning Art Nouveau buildings, clustered on Alberta Street in an area just northeast of Old Town, were designed by Jewish architect Mikhail Eisenstein, father of the famous filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. Art Nouveau architecture comprises about 40 percent of the buildings in central Riga.

History

Jews came relatively late to what is now Latvia; in the early fourteenth century they had been banned from settling in the region by an official decree of the ruling Master of the German Order. Some began to settle in the eastern part of the country in 1561 when that area fell under Polish rule, but in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries only the most successful were given permission to reside in Riga. Even so, they were forced to live in special inns called Judenherberge and were not allowed to be buried in the city.

Remnants of Riga’s Big Choral Synagogue. More than 300 Jews perished here in 1941.

Consequently, Jews had to shuttle their dead to graveyards in Poland until 1725, when they were finally given permission to build a cemetery. Still, by the mideighteenth century, Riga had just a few hundred Jewish residents. (In contrast, neighboring Lithuania was much more hospitable at the time and its largest city, Vilnius, became one of the most vibrant Jewish communities in all of Europe.)

Despite a number of restrictions on buying land, choice of profession and education, by the eighteenth century Jews began to have an economic and cultural impact. They became expert craftsmen and prominent in such fields as timber, finance and medicine. Most of the city’s Jews lived in a ghetto in an area called Maskavas, less than a mile southeast of Old Town (due to Nazi destruction, there are few remnants today of the ghetto). In the nineteenth century, restrictions on Jews were eased and many began to move out of Maskavas into other parts of the city. By 1897, there were more than 20,000 Jews living in Riga, about 8 percent of the city’s population.

Jews played a prominent role in the formation of an independent Latvian state between the two world wars. During this period, Jewish schools, theaters and newspapers thrived. From 1920 to 1935, the number of Jews in Riga grew from 24,000 to an all-time high of 44,000, more than 11 percent of the city’s inhabitants. At one time, there were as many as 14 synagogues. Riga even briefly became a focal point of the global Lubavitch movement in the late 1920’s when the Latvian government gave shelter and citizenship to its leader, Joseph I. Schneersohn, who had been exiled from the Soviet Union. From Latvia, the rebbe went to Poland before emigrating to the United States.

Memorial at the Big Choral Synagogue, which was destroyed by the Nazis in 1941.

In 1940, the Red Army entered Riga and leading Jewish political and religious leaders were arrested. About 5,000 Jews were among the thousands of Latvians deported to Siberia. Riga fell to the Germans on July 1, 1941, and Nazi atrocities against the Jews began that day when hundreds were executed as “retribution” for the Germans who were killed during the taking of Old Town. One of the most horrific crimes during the Nazi occupation of Latvia took place just three days later. On July 4, 1941, more than 300 Jews—many of whom were refugees from Lithuania—were herded into the basement of the Big Choral Synagogue. German soldiers threw grenades into the windows and the building was burned down. There were no survivors.

Some 77,000 Jews from Latvia, and 30,000 to 40,000 more who were transported from other countries in Nazi-occupied Europe, were killed on Latvian soil. Many were marched from the Riga ghetto in the winter of 1941-1942 to the Rumbula and Bikernieku forests, a few miles from the city center. There they were shot at a rate of up to 1,000 per hour, falling on top of those who had died before. Many of the killers were members of the local Latvian police force. Jews also perished at the Kaiserwald prison camp in the suburb of Mezaparks and at the Salaspils concentration camp 12 miles southeast of Riga. Only about 150 of Riga’s Jews survived the war. Some were saved by local residents; others managed to survive until the Red Army recaptured the city in the summer of 1944.

The end of the war brought the return of thousands of Latvian Jews who had fled to the Soviet Union to escape the Nazis. Other Jews from throughout the Soviet Union also settled in Riga. In the 1970’s, Riga became a major center of Jewish dissident activity. By 1989, just prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Riga’s Jewish population had climbed to about 23,000, a number that has steadily dwindled in recent years, as many Jews have emigrated to Israel, Great Britain and the United States. Of those who remain, more than a third do not hold Latvian citizenship due to restrictive naturalization laws enacted after independence that were aimed at the country’s large Russian minority. Such laws have been eased in the past few years, although applicants for citizenship still must pass a Latvian language test.

Community

Riga’s Jewish community is well organized in a model resembling Jewish federations in American cities. Religious life is headed by Rabbi Nathan Barkan, chief rabbi of Riga and Latvia. There are a number of Jewish schools in Riga that educate several hundred students at all age levels, a Jewish hospital and numerous organizations representing Jewish interests.

Under the guidance of Rabbi Mordechai Glazman, Chabad has had an active presence in Riga for more than 10 years. The organization runs Jewish schools and summer camps, helps feed the poor, holds a community Seder each Passover, erects a sukka in one of Riga’s main parks and otherwise attempts to rekindle Jewish traditions that were largely dormant during Soviet times.

One of the more visible components of Riga’s Jewish community is the Center for Judaic Studies, created in 1998 and housed in the University of Latvia’s main building at Rainis Boulevard 19 (e-mail: ad@lanet.lv). Headed by Professor Ruvin Ferber, the center offers courses in Jewish history, tradition and philosophy. It has a small library and every two years organizes an international conference called “Jews in a Changing World.” Notably, the opening ceremony to the 2001 conference drew the Latvian government’s president, past president, prime minister and several cabinet ministers.

Latvian President Vaira Vike-Freiberga initiated a Holocaust education program in the country’s schools.

Relations between the Latvian government and the Jewish community have been on solid footing in recent years. Latvia’s popular president, Vaira Vike-Freiberga, one of the few women heads of state in the world, has been vocal in her support of the Jewish community and has initiated a Holocaust education program in the schools. Sadly, though, the government has not successfully prosecuted any Latvian war criminals, and until recently failed to acknowledge the atrocities committed by Latvian collaborators during the Holocaust.

Sights

Riga’s sole surviving synagogue, the Peitav Shul, celebrates its 100-year anniversary in 2005.

The Peitav Shul, Riga’s sole surviving synagogue.

Located at Peitavas 6/8 (telephone: 011-371-722-4549), this tall, narrow Orthodox prayer house is tightly wedged between other buildings in Old Town, a fact that likely saved it from Nazi destruction. It is believed that the Nazis would have burned it down as they did the other synagogues, but its proximity to neighboring buildings made them afraid to set it afire. Instead, they converted it into a warehouse and horse stall. The synagogue features a traditional two-story interior—women pray upstairs—and there is a small display in the lobby with items about Latvia’s Jewish community.

About a 15-minute walk from the Peitav Shul, at the busy intersection of Gogola and Dzirnavu Streets, stands the remains of the Big Choral Synagogue. In 1988, a large gray memorial stone was placed a few feet from the synagogue’s surviving brick foundation. It is not uncommon to see flowers and candles at the base of the memorial.

The Jewish Community Center, known locally as Aleph, is located in the central part of the city at Skolas 6 (371-728-9580). The building dates back to before World War I and once housed a Jewish theater. It assumed its current function in 2000 with financial support from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

The building’s third floor houses a small but informative museum called The Jews in Latvia (371-728-3484; open Sunday through Thursday 12 to 5), which chronicles the history of Jewish life in Latvia going back to the eighteenth century. Exhibits show the many contributions of Jews in Latvian society, as well as the suffering experienced at the hands of the Nazis and Soviets. An uplifting section called “The Jewish People Survived” showcases the rebirth of Jewish life in Latvia since independence. At the entrance to the museum, visitors can purchase maps that identify the locations of former Jewish sites in Riga, including the Old Jewish Cemetery on Liksnas Street, which was destroyed by the Nazis and later converted by the Soviets into the Park of the Communist Brigades.

Two memorials, recently erected in forests just outside Riga, have brought renewed attention to the Holocaust in Latvia. In 2001, one was dedicated in the Bikernieku forest, where about 30,000 Jews perished in 1942. Funded in part by a German charitable fund, the memorial consists of a white altar surrounded by jagged rocks. Each section of rocks represents a liquidated Jewish community from where the victims originated.

The memorial in the Bikernieku Forest outside of Riga, where about 30,000 Jews were killed in 1942.

In November 2002, another memorial was unveiled at the Rumbula forest, where about 25,000 Jews were murdered in 1941. Significantly, the Rumbula monument acknowledges the involvement of the local population in the massacre. President Vike-Freiberga, who attended the dedication ceremony, called it “a day of mourning for all of Latvia because this crime happened on our soil and our people took part in it.” The memorial, funded by donations from Germany, Israel, Latvia and the United States, includes a large menorah surrounded by miniature obelisks bearing victims’ names.

Riga’s most impressive museum, the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia (Streinieku laukums 1; 371-721-2715; closed Mondays), thoroughly documents the destruction of Latvian sovereignty by the Soviets and Nazis. Located near the Daugava River in Old Town in a building that looks like a big black box, the museum includes historical documents, artifacts, pictures and a replica of a barracks in a Siberian Soviet prison camp where thousands of Latvians were deported. There is also a small section devoted to the Holocaust, including a display of Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda.

Other Sights

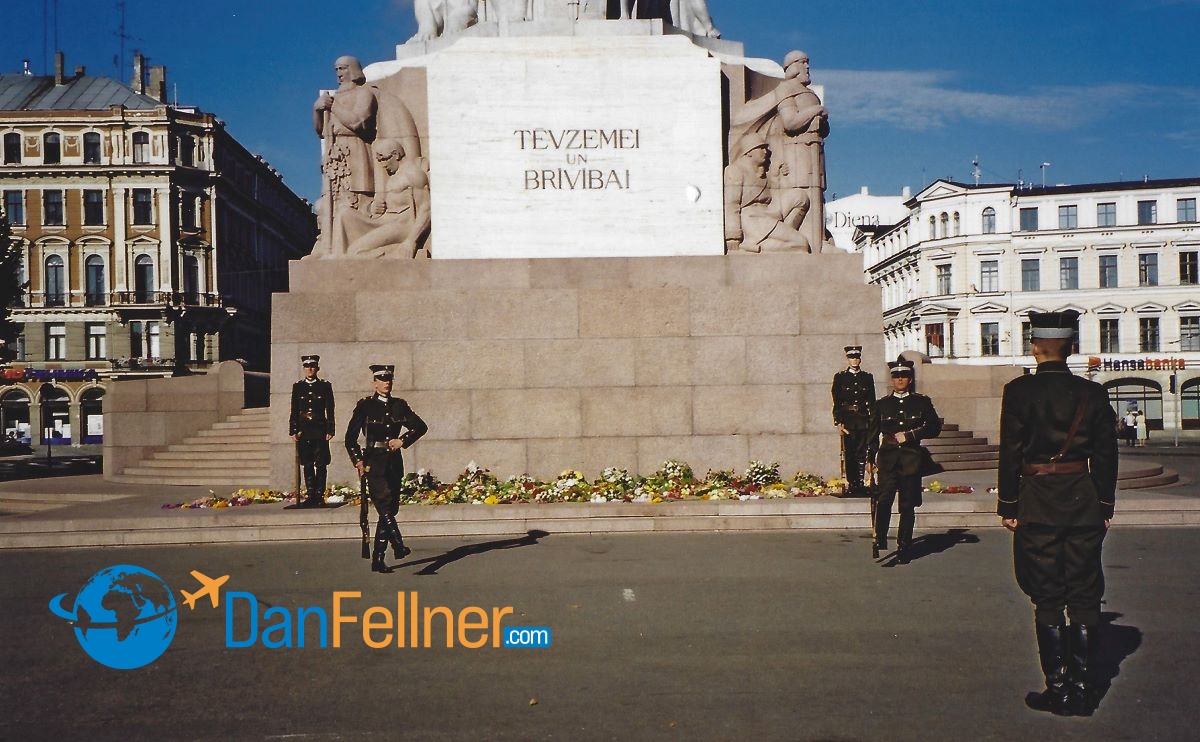

Given the country’s history, it’s not hard to understand why Riga’s Freedom Monument is such an important symbol to Latvians. Erected in 1935 and located at the intersection of Brivibas and Raina Streets just east of Old Town, the monument is topped by a bronze female statue affectionately called Milda by the locals and bears the Latvian inscription Tevzemei un Brivibai (For Fatherland and Freedom). Two soldiers guard the monument and there’s an hourly changing-of-the-guard ceremony. Latvians regularly lay flowers at the base of the monument to honor the victims of totalitarianism. It is said that those who dared to do so during Soviet times ended up with an extended, all-expenses paid vacation to Siberia.

Changing of the guard ceremony at Riga’s Freedom Monument.

For a magnificent view of Old Town from above, visit the thirteenth-century St. Peter’s Church (Skarnu 19). There’s an elevator that goes to the top of the spire, which at one time was the highest tower in Europe. Another impressive church in Old Town is the red-brick Dome Cathedral, the largest place of worship in the Baltics. It also dates back to the thirteenth century and now houses a 6,768-pipe organ, the fourth largest in the world.

The best place for shoppers to spend a lat (as the local money is called) or two is the centraltirgus, or central market, one of Europe’s largest and most colorful markets. It is housed in and around five huge buildings that were used as zeppelin hangars during World War I. There are more than 1,000 vendors, selling everything from fresh meat and produce to bootleg CD’s and fake Rolex watches. Amber jewelry is the most pervasive item sold in Riga’s souvenir shops.

Side Trips

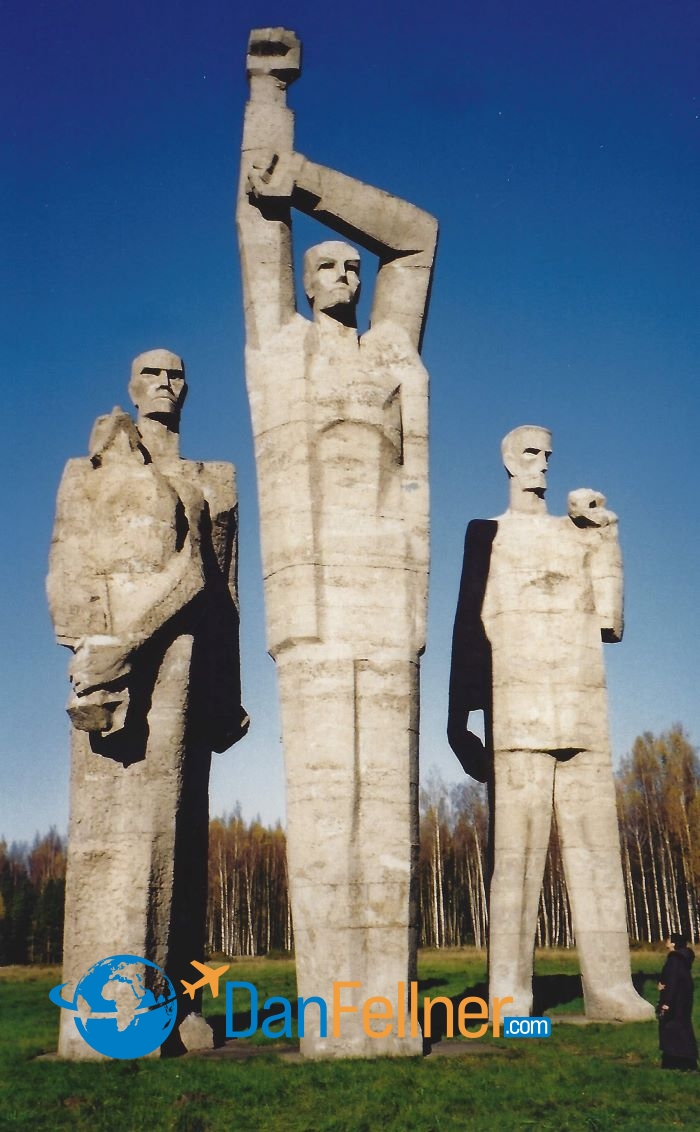

In the Salaspils concentration camp where tens of thousands of people were murdered, visitors aregreeted by a huge concrete wall bearing the words: “Beyond these gates the earth groans.”

Large sculptures at the Salaspils concentration camp, a 30-minute drive from Riga.

On the grounds inside stand several large sculptures that evoke the suffering and defiance of the camp’s victims. A metronome inside a long block of polished stone ticks endlessly, a haunting echo of the hearts that once beat at the camp. Salaspils is a half-hour drive from Riga, or you can take a train to the Darzini station and then walk on a path through the woods for about 20 minutes to the memorial.

Known as the “Switzerland of Latvia,” Sigulda, a small town 90 minutes east by train, is one of the most popular day-trip destinations from Riga. With hills instead of mountains, Sigulda may not entirely deserve such a nickname. But it is a great place for hikers to explore, with sandstone caves, lakes and a picturesque wooded valley dissected by the Gauja River. Sigulda also features the impressive red-brick Turaida Castle, which dates back to 1214.

The Turaida Castle in Sigulda dates back to 1214.

Reading

The Latvians: A Short History (Hoover Institution Press) by Andrejs Plakans gives a good overview of Latvian history from medieval times to the mid-1990’s, with an emphasis on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Max Michelson’s City of Life, City of Death: Memories of Riga (University Press of Colorado) chronicles his experiences and ultimate survival in Riga’s Jewish ghetto during the Nazi occupation.

Latvia: The Bradt Travel Guide is one of the few guidebooks devoted specifically to Latvia. Riga in Your Pocket, a small booklet sold in Riga hotels and souvenir shops (it can also be viewed on the Internet: www.inyourpocket. com/latvia/riga/en), provides up-to-date information about sightseeing, hotels and restaurants.

Recommendations

One of Old Riga’s most comfortable and reasonably priced hotels is the Radi un Draugi (Friends and Relatives). Owned and run by British Latvians, the hotel is just a block away from the Pietav Shul and offers clean and quiet rooms (371-722-0372; fax: 371-724-2239; e-mail: radi@drau gi.lv). More upscale and located in the city center not far from the Jewish Community Center is the Reval Hotel Latvija, one of Riga’s largest and poshest hotels (371-777-2222; fax: 371-777-2221; e-mail: latvija.sales@revalhotels.com). The bar on the twenty-sixth floor offers a wonderful panoramic view of the city.

For kosher food, Café Lechaim (371-728-0235; entrance on Dzirnavu Street) is a small restaurant located in a corner basement of the Jewish Community Center. The food is simple and cheap. Shalom (371-736-4911), a five-minute taxi ride away at A. Briana 10, offers nonkosher Jewish dishes. Look for blue neon Stars of David in the front window.

Riga isn’t the easiest place to get to. There are no direct flights from the United States and its fairly remote location in northeastern Europe makes it a long bus or train ride from other major European cities. But it’s well worth taking a side trip from places like London, Moscow, Stockholm, Helsinki, Copenhagen, Frankfurt, Warsaw or Prague, all of which offer nonstop flights into Riga. It’s a rare chance to see an alluring, vibrant and historic city that is yet untarnished by hordes of tourists.

A street musician performs in Riga’s Old Town.

© 2008 Dan Fellner