Fervent fans support a sport rich in history

The Arizona Republic — May 29, 2012

TOKYO – With an upper-deck ticket tucked away in my back pocket, I arrived 4 1/2 hours early for a late-April Sunday afternoon game between the Yomiuri Giants and Hanshin Tigers at the Tokyo Dome.

Japanese baseball fans waiting for standing room tickets outside the Tokyo Dome.

It was my first Japanese baseball game, and I wanted plenty of time to explore the Dome’s environs and visit the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, which adjoins the stadium.

I assumed the complex would be relatively deserted at 9:30 a.m., but after a five-minute walk from the train station, I couldn’t believe what I saw as I approached the Dome. Several hundred people — some of whom had appeared to have camped out the night before — were in an orderly line snaking up to a ticket window that hadn’t even opened yet.

The Tokyo Dome is the most-recognizable venue for baseball in Japan.

They were hoping to get standing-room tickets for that afternoon’s game. Only about half of them would eventually get inside the stadium, and even then, their view of the action would be blocked by so many people standing in front of them, they would end up watching the game on one of the many TVs located throughout the Dome’s concourse.

True, it was a holiday weekend in Japan and the Giants and Tigers are two of the country’s most popular teams. But I had not expected to see this level of interest for a regular-season game just three weeks into the season between the third- and fifth-place teams in a six-team league.

Once I went inside the Dome, I was even more surprised at the depth of the fans’ passion for a game the baseball-crazy Japanese call yakyu. From the first pitch through the final out, the intensity of the fans was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced at an American baseball game. I wasn’t sure if it felt more like being in the stands at an SEC football game or a zealot-packed political rally.

Entrance to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at the Tokyo Dome.

“It’s much noisier than Major League Baseball games,” said Wayne Graczyk, the dean of American baseball writers in Japan, who I met after the game for pizza and beer at a sports bar near the Dome. Graczyk first began writing about Japanese baseball in 1975 and is now a baseball columnist for the English-language Japan Times. He also is the longtime editor of the Japan Baseball Media Guide.

“Whatever the reason, since the early 1900s when colleges here first started playing baseball, it hooked on, and it’s been a passion of the Japanese people ever since,” he said.

This day at the Dome proved to be my most memorable experience during a weeklong trip to Tokyo. With its labyrinth of trains and subways and dearth of English street signs, the world’s largest metropolitan area — home to more than 30 million people — can be bewildering and even downright intimidating to foreigners. Going to a ballgame brought a much-needed sense of familiarity, and at the same time, offered a fascinating glimpse into Japanese culture.

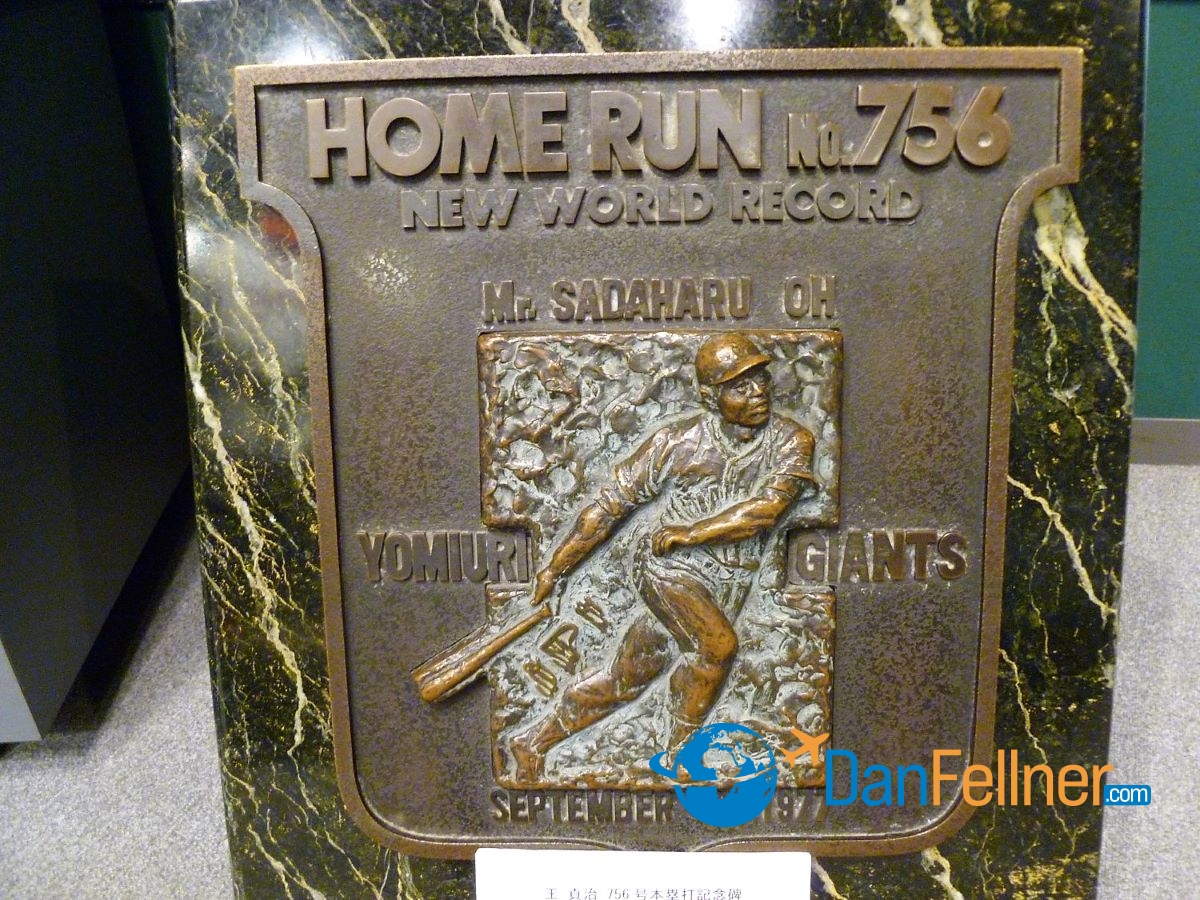

A plaque honoring Sadaharu Oh in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame.

Before the game, I spent a couple of hours touring the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. I learned that baseball started here in 1872 when Horace Wilson, an American teacher living in Tokyo, wanted to come up with a way for his students to get more exercise. So he taught them to play baseball. Wilson was posthumously elected to the Japanese Hall of Fame in 2003.

Also enshrined is Sadaharu Oh, the only Japanese player I had ever heard of before pitchers Hideo Nomo and Hideki Irabu were signed by major-league teams in the 1990s. Known for his distinctive “flamingo” leg kick, Oh holds the world career home run record of 868, 106 more than Barry Bonds. Oh played his entire 22-year career with the Yomiuri Giants, retired in 1980 and later became the Giants’ manager.

Like any good sports museum, there’s an interactive exhibit in which visitors can test their skills against some of the greats of the game. In this case, they’ve set up a virtual batting cage with a video screen displaying some of Japan’s toughest pitchers in their windup. You get three swings at the screen with a small plastic bat. A cardboard-cutout umpire connected to a computer announces if you made contact.

Facing Japanese pitching greats in the Hall of Fame’s virtual batting cage.

Luck of the draw, I went up against Yu Darvish, perhaps the most intimidating pitcher in Japanese history. Before joining the Texas Rangers this season, Darvish pitched from 2005-11 for the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, compiling a nifty 93-38 record with an ERA of 1.99.

I gave Darvish no trouble. “Batter out,” the cardboard umpire barked in barely discernible English after I swung and missed for the third time. The next batter was a Japanese boy who looked to be about 12. He promptly doubled off the wall.

The first thing visitors see when entering the museum is a trophy case full of memorabilia from the inaugural two World Baseball Classics in 2006 and 2009, both of which were won by Japan. It made me wonder about the quality of play in Japan. How does it compare to American baseball?

Exhibits at the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo.

“A lot of people ask me about the level of play here,” said Graczyk. “It’s higher than Triple-A, but lower than the major leagues.”

And what about the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks, winners of last year’s Japan Series, Nippon Professional Baseball’s equivalent of the World Series? How would they have fared in the majors?

“I don’t think they would have made the postseason,” he said. Would they have had a winning record? “Probably not.” But Graczyk added that he thought there are enough high-caliber players in the country — as evidenced by the success players such as Darvish and Ichiro Suzuki have enjoyed in the U.S. — that a Japanese all-star team could possibly make the playoffs in MLB.

It was now two hours before game time — when they were scheduled to open the gates — and a large crowd was already lined up waiting to get inside. Before going in, I walked over to the Tokyo Dome Hotel and rode an elevator up the 40th floor for a better view of the stadium. I could see why the Dome, which opened in 1988 and was the first covered baseball venue in Japan, is commonly referred to as “The Big Egg.” From above, that’s exactly what it looks like.

View of “The Big Egg” from the Tokyo Dome Hotel.

I was surprised to learn that the Arizona State football team once played a game at the Tokyo Dome. In 1990 ASU faced the University of Houston in a regular-season game called the “Coca Cola Bowl.” Apparently the Sun Devils’ secondary was suffering from a severe case of jetlag. They gave up 716 yards in the air by Houston quarterback David Klingler in a 62-45 loss, a record that still stands as the most passing yards in an NCAA game.

After grabbing a quick lunch of traditional Japanese noodle soup at a stand outside the stadium, I entered the Tokyo Dome. From the inside, it looked comparable to most of the cookie-cutter domed stadiums built in America in the 1980s. Functional, but not exactly bursting with personality.

I took a walk around the concourse to check out the concession stands. They had all the usual ballpark fare found back home, including hot dogs, hamburgers and ice cream. But the stand that seemed to be the busiest was selling something you won’t find at Chase Field — a bento box. This is a traditional Japanese meal served in a plastic box. You get some sort of fish or meat, rice, pickled vegetables and other local delicacies that you likely won’t be able to discern, each in their own compartment.

A bento box concession stand inside the Tokyo Dome.

I had tried a bento box a couple of days before in Tokyo. Even though I had struggled with the chopsticks, it made for a quick and tasty lunch. I had paid 400 yen (about $5) for mine, about one-third of what they were charging at the Tokyo Dome.

In addition to domed stadiums, artificial turf and the designated hitter, it seems the Japanese have imported something else from American baseball — the art of concession-stand price gouging.

The Dome was filling up and I took my seat. Before coming to Japan, I had looked on a map to find where the cities of Yomiuri and Hanshin are located. Then I found out that many Japanese teams aren’t named for the cities in which they’re located, but rather their corporate owners. Yomiuri is a huge Japanese media conglomerate and Hanshin is a railway company.

The starting lineups on the Tokyo Dome’s scoreboard.

The Giants, though, are most closely associated with Tokyo, and the Tigers play their home games near Osaka. Graczyk told me the Giants — historically the most successful franchise in Japanese baseball — are somewhat akin to the New York Yankees. People either love them or hate them.

I had gotten a sense of this at my hotel that morning when I told Iida, the front-desk clerk, I was going to the game. Iida barely spoke English but he had no trouble summoning the words when I asked him if he rooted for the Giants. “No,” he said without hesitation. “Why not?” I asked. “Giants are here,” he said, with his hand at eye-level. “I like the teams here,” he added, dropping his hand a couple of feet.

Explained Graczyk: “A lot of people here like to root for the underdog.”

The Yomiuri Giants face the Hanshin Tigers in a sold-out Tokyo Dome.

The Yomiuri Giants’ uniforms closely resemble the uniforms worn by their American namesake — the San Francisco Giants. Being a loyal Diamondbacks fan, I decided to root against them, too.

The Giants were the home team, but it seemed as if the stadium was equally split between supporters of the two teams. I happened to be surrounded mostly by Tigers fans, many of whom were wearing yellow, while Giants’ fans were dressed in orange. The stadium looked like a giant citrus orchard.

Once the game started, the noise was incessant. There was the constant clanking together of miniature plastic bats with team logos that many fans had brought with them. There also was chanting and singing in unison, orchestrated from each team’s cheering section in the outfield bleachers. Known as an oendan, these sections were the epicenters of organized cheers that reverberated throughout the stadium.

Diehard fans root for the Yomiuri Giants in the Tokyo Dome.

I had no idea what the fans were chanting and singing, just that it was loud and in unison. I asked the people sitting next to me to translate the cheers for me, but no one seemed to speak English.

Finally, in the bottom of the second inning, as Giants pitcher Tetsuya Utsumi walked to the plate (there are two six-team leagues in Nippon Professional Baseball; the Pacific League uses the DH, while the Central League — which includes the Giants and Tigers — does not) the crowd broke out in a song I could understand — “Happy Birthday.”

Turned out, it was Utsumi’s 30th birthday.

Later in the game, I took a walk to get a closer look at the Tigers’ oendan in the left-field bleachers. Huge flags were being waved and I heard drums, tambourines and trumpets making music under the direction of a fan holding signs in the front row — like the captain of a cheerleading squad at a college football game. The colors, songs and cheers were different, but the same thing was going on in the right-field bleachers, the heart of the Giants’ oendan.

The Hanshin Tigers’ oendan in the left-field bleachers.

What I saw on the field didn’t look much different than back home. There are only a few major rules differences between Japanese and American baseball. The regular season in Japan is 144 games, compared to 162 in the U.S. Japanese teams are each allowed a maximum of four foreign players. And if an extra-inning game in Japan is still tied after three-and-a-half hours, they won’t start a new inning and the game ends in a tie. Games lasting into the early morning hours just don’t work in Japan.

“Around the Tokyo Dome, there’s no parking,” Graczyk said. “Everybody comes to the game by train. And the trains stop running shortly after midnight.”

The Yomiuri Giants beat the Hanshin Tigers, 2-0.

Utsumi celebrated his birthday by throwing seven scoreless innings and the Giants won, 2-0. After the victory, the Giants’ players bowed in unison to their fans. The following day the two teams played to an 11-inning scoreless tie. Offensive production is way down in Japan the past two seasons; some believe the decline stems from a change to a less-lively baseball introduced at the start of the 2011 season.

Tokyo is one of the most expensive cities in the world. A decent-quality sushi dinner can easily cost $100. A movie theater ticket is $24. Even a cup of tea can set you back $5.

But baseball is a relative bargain, with prices comparable to what you’d pay to see a Major League game. I purchased my seat — behind home plate 10 rows from the top of the stadium — several weeks earlier online for 2,300 yen (about $29). When I bought the ticket in early April, there were only a handful of seats available in the entire 42,000-seat Dome. More than 3,000 fans were admitted with standing-room tickets, pushing the paid attendance to 45,164.

Mascots and cheerleaders perform between innings at the Tokyo Dome.

The Hall of Fame also is reasonably priced. Admission is just 500 yen ($6.25) and they’ll give you a 20 percent discount if you present a ticket for that day’s game.

I’ve attended a hockey game in Latvia, kickboxing in Thailand, and a soccer match in Brazil. Going to a sports event abroad — like a Japanese baseball game — can often give insight into a culture that you just can’t get in a museum, castle or religious shrine.

In addition to writing about baseball, Graczyk works for a company — JapanBall.com — that offers baseball tours in which visitors can attend games in all 12 Japanese big-league ballparks.

“It’s one of the things you should see when you come to Japan,” said Graczyk. “It’s just an awesome experience.”

© 2018 Dan Fellner